It’s been a while I haven’t posted any items. This is partly due to increase in work load, and more so, just being lazy to write. I hope to continue to write.

Anyway, the other day I noticed a news item on ekantipur online. The news was about the closure of the revered Ranjana Cinema Hall, and the reflections of the Hall owner, who apparently was sad to see it closed. An air of nostalgia hit my senses, I reminisced the many wonderful movies I had seen in Ranjana.

Perhaps the most unique thing about Ranjana was how every show would start with a “ding dong…” type music; Ranjana was the only theater in the valley to begin the show with this music. For me, the music was always a great way, a prelude, to the fantastic things that would follow on the silver screen. The yellow spot lights focused on the screen had a strange calming effect. The music would heighten my senses (both aural and visual) with exhilaration and anticipation. The feelings were somewhat similar to the excitement created by up and coming singers who open for great rock artists at music concerts.

Some of the memorable movies that I had seen in Ranjana were Aradhana, Amar Prem, Anand, Jaise Ko Taisa, and the horror movie “Bees Saal Pahale” (Twenty Years Ago). My friends in town had warned me not to see the movie alone, as it was supposedly very scary. I liked horror movies, so decided to see the movie with a friend who lived in Maha Bouddha (close to Ranjana). Don’t know how it happened but we ended up watching the evening (6-9) show. My friend chickened out mid-way, but I decided to continue even though I was scared. The thought of having to walk home alone after the show made me panic, but I could not resist the temptation of finishing the movie.

By the time the movie ended, I was totally scared, the climax scene shows how the ghost (shown as a complete human skeleton) of the murdered heroine kills the villain, as she comes behind him and strangles his neck. The outcome was very satisfying but by now I truly dreaded walking home all by myself. The walk home was perhaps the longest that I had ever felt – it was only 20 minutes to home – but it felt as if it was an eternity. A few people who walked out together went in different directions. I kicked up my pace and negotiated the narrow streets of Indrachowk and Thahiti carefully, avoiding eye contacts with anyone who could be around at that ungodly hour. A section of the street near Chetrapati was dark (the streetlights there never seemed to work - work of the ghosts perhaps), and many people in my neighborhood had thought that part of the street haunted. I began to sweat as I came closer to that street, and nervously looked around to see if anyone was following me. My chest started to pound, and I started running. My eyes were closed, fists stiff, palms locked in tight, sweat dripping from my forehead, adrenaline rushing into my brain. I could hear my heavy breathing. I sped as fast as I could. As I reached Saunepati, I saw the flicker of lights in houses, lights streaming from the windows onto the street. The streetlights were working, darkness slowly disappeared. I felt I had escaped from the clutches of the ghost. Phew! What an evening was that, an evening I vividly remember to this day.

Anyway, movies in Ranjana were so fun to watch, it showed some of the best movies of the year. Alas! it no longer exists. An important cultural icon has succumbed to the vagaries of modern times, biting the dust a multi-story building is planned), its memorabilia joining the relics of history. Ranjana will always have an affectionate place in my heart and will remain lodged into my memories.

Saturday, October 9, 2010

Saturday, December 5, 2009

A mountain charm

A couple of days ago, I had the opportunity to visit Shimla in India to attend a conference. I had heard about Shimla since my childhood days (one of my aunts had lived there during the 60s). The movie “Aradhana” which I mentioned in my previous posting, was filmed there including picturising the famous song “Mere sapno ki rani..”. Shimla turned out to be a very charming mountain city. The Brits had chosen it as a place to escape from the scorching summer in New Delhi or Calcutta (the capital city during British Raj), so they developed it as a “hill station”. The colonial imprint is everywhere – the road and rail infrastructure, the buildings (tudor and neo-gothic architecture), street names, names of government buildings etc. One of the longest narrow gauge railway in India brings tourists to Shimla from Kalka. The city today is the state capital of Himachal Pradesh, and as such has grown considerably because of employment prospects, tourism and other entrepreneurial opportunities. I found it to be a very clean city, its people very friendly and its culture similar to those found in the highlands of Nepal. Indeed, the Gurkha empire in its prime had extended its power to these regions, and I was told, their descendants still live there. On the streets, I heard people talking in Nepali and other local dialouges which sounded very much like the languages spoken in the far western mountain regions of Nepal.

The main market center in Shimla is anchored by a historic church located at an altitude of 7200 ft. I went inside the church, and read some of the plaques posted there describing the early pioneers of Shimla, for example, the first British principal of the convent school. Two life size statues of Mahatma Gandhi and Indira Gandhi were nearby. Looking across the city and over in the northerly direction, you could see the snow-capped mountains. Shimla has the atmosphere of a major city tucked high up on the mountains, its little charms include the “Mall” a pedestrian-only street that stretches from the State Parliament building and through the main streets lined with shops enticing tourists to buy local made textiles, general consumer goods, restaurants (yes, Chinese and Mexican too!), banks, western union, etc. I was delighted to see so many people walking, chatting, and just milling around and basking in the afternoon sun. There was something warm about the place and the people, a welcoming environment, which you don’t feel when visiting other big cities whether in India or overseas. I felt I was in a familiar surrounding and decided right there that should an opportunity come in the future I would return to this place again and expore it some more. The snowcapped mountains were inviting me, and I imagined myself someday on a drive or trekking tour to the land of Leh in Laddakh, not very far away from Shimla.

The main market center in Shimla is anchored by a historic church located at an altitude of 7200 ft. I went inside the church, and read some of the plaques posted there describing the early pioneers of Shimla, for example, the first British principal of the convent school. Two life size statues of Mahatma Gandhi and Indira Gandhi were nearby. Looking across the city and over in the northerly direction, you could see the snow-capped mountains. Shimla has the atmosphere of a major city tucked high up on the mountains, its little charms include the “Mall” a pedestrian-only street that stretches from the State Parliament building and through the main streets lined with shops enticing tourists to buy local made textiles, general consumer goods, restaurants (yes, Chinese and Mexican too!), banks, western union, etc. I was delighted to see so many people walking, chatting, and just milling around and basking in the afternoon sun. There was something warm about the place and the people, a welcoming environment, which you don’t feel when visiting other big cities whether in India or overseas. I felt I was in a familiar surrounding and decided right there that should an opportunity come in the future I would return to this place again and expore it some more. The snowcapped mountains were inviting me, and I imagined myself someday on a drive or trekking tour to the land of Leh in Laddakh, not very far away from Shimla.

"The Queen of my dreams..."

Speaking of music and songs, I like to harken back to the late 60s and early 70s. Growing up, I was fascinated by Bollywood movies, who wasn’t back then? They were the only forms of entertainment during those days, and in my grandfather I found one of the biggest fans of Bollywood movies. Every movie he watched, I was with him. I cannot remember some of my earliest movies but I have vague recollections of songs from those movies, for example, “Hum Kale hain to kya huwa dilwale hain..” (I don’t care I am dark-skinned, I have a generous heart) from the movie “Balak”, and “Yeh nargise mastana! basa itni batade tu..” (Hey beautiful! just tell me…) from the blockbuster “Aarju”. Rajendra Kumar, the hero of Aarju was famous and I wanted my mom to part my hair just like Rajendra Kumar’s. I must have been five or six years old. I could sing the songs from these movies and I quickly became the entertainer in my family. There wasn’t a time when I wasn’t humming some tunes from the latest flick. Then in 1969 “Aaradhana” was released, the movie gave rise to the phenomenon “Rajesh Khanna”, who became the first ever Bollywood superstar. He was a romantic hero and sang “Mere sapnoki rani kab aayegi tu..” (The queen of my dreams when will you come to me..”, which instantly became the number one song of the year and declared the supremacy of Kishore Kumar in Hindi music scene. While Kishore had been singing Hindi songs for several years, he played second fiddle to Mohammed Rafi who was hugely popular. 1969 was the beginning of the rise of Kishore Kumar and the declining popularity of Rafi. I was immediately struck by Kishore’s style of singing, his guttural voice and easy manners. I became his fan and to this day, I remain his most loyal fan.

So I started singing “Mere sapno ki rani..” and other Kishore songs. I could sing it well and my talent was quickly recognized at home, in the neighborhood, and at school. I was an eight year old kid, I did not have any inhibitions when it came to singing. If somebody asked me to sing, I would start right away. I don’t know how the school principal found out that I could sing, so when I was in Grade 5 I was asked to sing during school functions. I must have sang well for I was now a fixture at the school’s cultural events. I did not know how to play instruments, something that I would regret later, but I could memorize full verses and then render the songs in a typical Kishore style. Singing led to watching movies, and movies to songs. Some of the most memorable times during that period was the day Crown Prince Dipendra was born. My neighbor Purna Dai took me from home, brought me with him to the ward office (municipal office), which was just next doors from ours, handed me the loudspeaker, have me sit in one of the chairs in the office and instructed me to sing whatever I could and for as long as I could. It was more like the people in my neighborhood wanted to express our happiness on that joyous occasion. I don’t remember how long I sang, but it sure felt like a long day, I must have been their singing non-stop for two-three hours. It was up to me to sing whatever I desired, and that meant singing the ones I knew very well, but also those which I knew only a short verse or so. I sure felt that my neighbors had recognized my talent. Perhaps I was chosen not because I was just a small kid, but I sure had the energy, enthusiasm, the voice and the patience that was demanded of me. Anyway, my rendering of Kishore Kumar’s romantic songs made me a local hero of sorts. From that day onward, everybody in my neighborhood knew me (I was Krishna Baje’s Nati – or my grandfather Krishna’s grandson). One of my friends continues to tease me with the song “Mere sapno ki rani…” whenever we meet.

So I started singing “Mere sapno ki rani..” and other Kishore songs. I could sing it well and my talent was quickly recognized at home, in the neighborhood, and at school. I was an eight year old kid, I did not have any inhibitions when it came to singing. If somebody asked me to sing, I would start right away. I don’t know how the school principal found out that I could sing, so when I was in Grade 5 I was asked to sing during school functions. I must have sang well for I was now a fixture at the school’s cultural events. I did not know how to play instruments, something that I would regret later, but I could memorize full verses and then render the songs in a typical Kishore style. Singing led to watching movies, and movies to songs. Some of the most memorable times during that period was the day Crown Prince Dipendra was born. My neighbor Purna Dai took me from home, brought me with him to the ward office (municipal office), which was just next doors from ours, handed me the loudspeaker, have me sit in one of the chairs in the office and instructed me to sing whatever I could and for as long as I could. It was more like the people in my neighborhood wanted to express our happiness on that joyous occasion. I don’t remember how long I sang, but it sure felt like a long day, I must have been their singing non-stop for two-three hours. It was up to me to sing whatever I desired, and that meant singing the ones I knew very well, but also those which I knew only a short verse or so. I sure felt that my neighbors had recognized my talent. Perhaps I was chosen not because I was just a small kid, but I sure had the energy, enthusiasm, the voice and the patience that was demanded of me. Anyway, my rendering of Kishore Kumar’s romantic songs made me a local hero of sorts. From that day onward, everybody in my neighborhood knew me (I was Krishna Baje’s Nati – or my grandfather Krishna’s grandson). One of my friends continues to tease me with the song “Mere sapno ki rani…” whenever we meet.

Sunday, October 4, 2009

City of Lights

Ok, now that Dashain is over, it’s time to talk about another biggest festival of the year – Tihar. While Dashain is considered as the festival when we eat lots and lots of meat, Tihar is when we eat lots and lots of sweets, all home made. Tihar, or its more formal name Deepawali, is a festival of lights. For three days, the city of Kathmandu turns into city of lights. Every doors and windows are lined with flickering candles and/or oil lamps. Set against the soft darkness of the Fall season, the whole city comes to life as if gods have descended upon it to rejoice and celebrate with the mortal beings. Tihar is very different from Dashain in that it does not involved ritual killings that I described in my previous post. Celebrated for five days, Tihar begins with celebrating the life of a crow – the crow, or Kag in Nepali – according to the Hindu mythology, the cawing of a crow symbolizes sadness or grief, so on the day of Kag Tihar people in Kathmandu try to attract the crow to their balcony or the roof by placing offerings of food. Interestingly, the Nepalese also believe that the cawing of a crow on your rooftop means a guest is likely to pay a visit to your house – there is no shortage of guests at your home during Tihar. Kag Tihar is followed by Kukur (dog) Tihar – the dog is considered a messenger of the god of death Yamaraj. According to the Hindu mythology, the dog escorts you to Yamraj’s gate and tries to guide and protect you from the perils of the journey that takes you to the Yamaraj. On this day, you will see dogs (even stray ones) pampered with sweets, and frolicking in the neighborhood wearing marigold garlands around their necks and red tika on their foreheads. Even the nasty dogs are shown a level of affection not usually common among most Kathmanduities when it comes to stray dogs. To everyone’s surprise the dogs do not engage in street brawls on that day, as if they are also in the mood to rejoice, celebrate and at peace with each other acknowledging the right to co-exist. The atmosphere on the streets of Kathmandu seems serene, harmonious and joyful.

The third day of Tihar is Gai (cow) Puja or Laxmi Puja. The mother cow is the holiest of all animals in Hindu mythology, the giver of precious milk to nourish our bodies, the manure to fertilize the earth, and in rural households to purify homes and courtyards with its manure. The cow symbolizes the spirit of kindness, and of motherly love. The cow is worshipped (tika on her forehead, marigold garland around her neck) and offered fruits and homemade sweets. The cow is also a manifestation of the goddess of wealth (Laxmi). In rural Nepal the number of milk giving cows in your livestock shed is often the barometer of your prosperity in the village. As most travelers to Nepal know, the cow is a mighty force even on the most congested streets of Kathmandu where she roams free, unobstructed, and with little care for the imminent dangers from cars, motorbikes, rickshaws and people. Anytime I am on the streets of Kathmandu, for example, on the highly congested section between Indrachowk and Kamalachhi, the sight of a cow and her carefree spirit instills in me a true sense of freedom, a realization that is most unrealizable, imagination that is anything but impossible. So we celebrate Gai Tihar with unflinching spirit and with a care that attains its highest level on that day. We watch her move around the neighborhood with grace, kindness, humility and pure freedom. Families engage in elaborate decorations of their entrances with small prints of Laxmi’s feet, hoping that she visits the house softly at night and brings prosperity to the families. On the fourth day, we celebrate Gobardhan Puja, or Goru (ox) puja. This is the day when farmers worship the mighty Goru, the one that ploughs the earth with its sheer strength and determination. Farmers have special affinity with the Goru, not only it is Lord Pashupati’s carrier, it is also the principal source of labor without which many farmers in the Nepalese hills and terai cannot till their lands.

On the fifth and the final day of Tihar, Bhai Tika is celebrated. Brothers and sisters throughout Nepal reunite and put tika on each other, sisters pray for their brothers’ safety, brothers promise to protect their sisters. Those without a brother or a sister visit the temple in Rani Pokhari, which is opened for public visit only on that day during the whole year. In my family the ritual of Bhaitika takes more than two or three hours. You see, I have four sisters, the tika ceremony is very elaborate, completed in stages starting with putting oil on my head the night before and culminating with the exchange of fruits and sweets the next day. The family ritual on the day of Bhaitika involves the sisters circumnavigating the brother (seated on the ground, legs crossed) and drawing a line of oil and water brushed by fresh dubo (a small clump of fresh grass neatly tied toether) around him, demarcating a boundary which no forces of evil can penetrate. Thereafter, they take turns in putting the multicolored tika on the forehead, the tika is put in a vertical row of red, blue, purple, yellow, green, and black colors. They put garlands of dubo, purple colored makhamali (Globe amaranth / Gomphrena globosa) and marigold flowers around the brother’s neck, give him fruits, homemade sweets (sel, anarsa, khajuri) and masala (dry spices - a mix of almonds, coconut, plum, cashew, etc). In return, the brother puts tika in similar fashion on the foreheads of his sister, starting from the eldest and to the youngest, gives them fruits, sweets and money. The ceremony ends with a family feast.

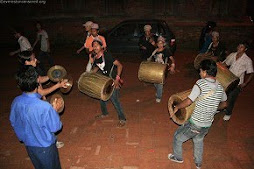

On the third and the fourth day, the night comes alive. This is the day when children and adults alike band together to form singing groups and visit different homes to sing Deusi (third day) and Bhailo (fourth day) in return for money and/or other offerings. The night is brightly lit with candles and oil lamps, there is music in the air, fireworks sparkle the night sky with radiant colors, children come out on the streets beautifully dressed, and peace and harmony litter the streets of Kathmandu. I participated in these events with almost a missionary zeal. We would plan singing days in advance, preparing a list of homes to visit, and in some cases sending them an advance notice that we would be coming to sing at their house. We would plan our lineup of songs (Deusi or Bhailo were the main songs, but we would also sing other popular Nepali folk and Bollywood songs), instruments to be played and determine who would be playing what. For Bollywood songs, I would be one of the lead vocalists. We would start visiting homes at seven in the evening or as soon as it is dark, working through our neighborhood and then moving on further. Depending on the size of the group (sometimes it would be around 6-7, but mostly it was more than 10 in the group), we would collect various amounts of money during the two nights. Often, we sang and played until mid-night. The money would be spent on some group activities, for example, a picnic at the outskirts of Kathmandu, planned in the days to come. One year, we had more than 20 in the group so we had to rent a minivan to go around, for example, we sang at the western entrance (Keshar Mahal) of the Royal Palace (we had to send a notice several days in advance) and at the Prime Ministers’ official residence in Baluwatar. The beauty of the Deusi song was that as long as you followed its rhythm you could sing almost about anything you wanted, which usually meant singing in praise of the family you were visiting, but also singing about the difficulty faced along our way to the house, our impatience with the time it has taken for the family to give their donations, etc. which were smartly built into our tunes. Our Deusi song went something like this:

Heh…jhilimili jhilla, deusi re!…(glitter galore, deusi re!)

Heh…tato roti milla, deusi re!…(hot bread (we shall receive) deusi re!)

Heh…rato mato, deusi re!…(red mud, deusi re!..)

Heh…chiplo bato, deusi re!…(slippery path, deusi re!…)

Heh…aayon hami, deusi re!… (we came, deusi re!..)

Heh…deusi gauna, deusi re!… (to sing deusi, deusi re!..)

Heh…yo ghar ko rani, deusi re!…(this home’s queen, deusi re!..)

Heh…Kasto ramro bani, deusi re!…(how nice is she, deusi re!..)

And the songs/tunes were played over and over until a family member emerged at the door with donations.

The Bhailo rhythms were different. It started with:

”..bhailini aaye angana, (the choir has come to your courtyard)

..guniyo cholo magan (to ask for a dress; guniyo=skirt, cholo=blouse)

..heh aunsi bara, (this day of the New Moon)

..gai ko tihar bhailo!...” (this cow tihar, bhailo!)

And the beat continued...

The third day of Tihar is Gai (cow) Puja or Laxmi Puja. The mother cow is the holiest of all animals in Hindu mythology, the giver of precious milk to nourish our bodies, the manure to fertilize the earth, and in rural households to purify homes and courtyards with its manure. The cow symbolizes the spirit of kindness, and of motherly love. The cow is worshipped (tika on her forehead, marigold garland around her neck) and offered fruits and homemade sweets. The cow is also a manifestation of the goddess of wealth (Laxmi). In rural Nepal the number of milk giving cows in your livestock shed is often the barometer of your prosperity in the village. As most travelers to Nepal know, the cow is a mighty force even on the most congested streets of Kathmandu where she roams free, unobstructed, and with little care for the imminent dangers from cars, motorbikes, rickshaws and people. Anytime I am on the streets of Kathmandu, for example, on the highly congested section between Indrachowk and Kamalachhi, the sight of a cow and her carefree spirit instills in me a true sense of freedom, a realization that is most unrealizable, imagination that is anything but impossible. So we celebrate Gai Tihar with unflinching spirit and with a care that attains its highest level on that day. We watch her move around the neighborhood with grace, kindness, humility and pure freedom. Families engage in elaborate decorations of their entrances with small prints of Laxmi’s feet, hoping that she visits the house softly at night and brings prosperity to the families. On the fourth day, we celebrate Gobardhan Puja, or Goru (ox) puja. This is the day when farmers worship the mighty Goru, the one that ploughs the earth with its sheer strength and determination. Farmers have special affinity with the Goru, not only it is Lord Pashupati’s carrier, it is also the principal source of labor without which many farmers in the Nepalese hills and terai cannot till their lands.

On the fifth and the final day of Tihar, Bhai Tika is celebrated. Brothers and sisters throughout Nepal reunite and put tika on each other, sisters pray for their brothers’ safety, brothers promise to protect their sisters. Those without a brother or a sister visit the temple in Rani Pokhari, which is opened for public visit only on that day during the whole year. In my family the ritual of Bhaitika takes more than two or three hours. You see, I have four sisters, the tika ceremony is very elaborate, completed in stages starting with putting oil on my head the night before and culminating with the exchange of fruits and sweets the next day. The family ritual on the day of Bhaitika involves the sisters circumnavigating the brother (seated on the ground, legs crossed) and drawing a line of oil and water brushed by fresh dubo (a small clump of fresh grass neatly tied toether) around him, demarcating a boundary which no forces of evil can penetrate. Thereafter, they take turns in putting the multicolored tika on the forehead, the tika is put in a vertical row of red, blue, purple, yellow, green, and black colors. They put garlands of dubo, purple colored makhamali (Globe amaranth / Gomphrena globosa) and marigold flowers around the brother’s neck, give him fruits, homemade sweets (sel, anarsa, khajuri) and masala (dry spices - a mix of almonds, coconut, plum, cashew, etc). In return, the brother puts tika in similar fashion on the foreheads of his sister, starting from the eldest and to the youngest, gives them fruits, sweets and money. The ceremony ends with a family feast.

On the third and the fourth day, the night comes alive. This is the day when children and adults alike band together to form singing groups and visit different homes to sing Deusi (third day) and Bhailo (fourth day) in return for money and/or other offerings. The night is brightly lit with candles and oil lamps, there is music in the air, fireworks sparkle the night sky with radiant colors, children come out on the streets beautifully dressed, and peace and harmony litter the streets of Kathmandu. I participated in these events with almost a missionary zeal. We would plan singing days in advance, preparing a list of homes to visit, and in some cases sending them an advance notice that we would be coming to sing at their house. We would plan our lineup of songs (Deusi or Bhailo were the main songs, but we would also sing other popular Nepali folk and Bollywood songs), instruments to be played and determine who would be playing what. For Bollywood songs, I would be one of the lead vocalists. We would start visiting homes at seven in the evening or as soon as it is dark, working through our neighborhood and then moving on further. Depending on the size of the group (sometimes it would be around 6-7, but mostly it was more than 10 in the group), we would collect various amounts of money during the two nights. Often, we sang and played until mid-night. The money would be spent on some group activities, for example, a picnic at the outskirts of Kathmandu, planned in the days to come. One year, we had more than 20 in the group so we had to rent a minivan to go around, for example, we sang at the western entrance (Keshar Mahal) of the Royal Palace (we had to send a notice several days in advance) and at the Prime Ministers’ official residence in Baluwatar. The beauty of the Deusi song was that as long as you followed its rhythm you could sing almost about anything you wanted, which usually meant singing in praise of the family you were visiting, but also singing about the difficulty faced along our way to the house, our impatience with the time it has taken for the family to give their donations, etc. which were smartly built into our tunes. Our Deusi song went something like this:

Heh…jhilimili jhilla, deusi re!…(glitter galore, deusi re!)

Heh…tato roti milla, deusi re!…(hot bread (we shall receive) deusi re!)

Heh…rato mato, deusi re!…(red mud, deusi re!..)

Heh…chiplo bato, deusi re!…(slippery path, deusi re!…)

Heh…aayon hami, deusi re!… (we came, deusi re!..)

Heh…deusi gauna, deusi re!… (to sing deusi, deusi re!..)

Heh…yo ghar ko rani, deusi re!…(this home’s queen, deusi re!..)

Heh…Kasto ramro bani, deusi re!…(how nice is she, deusi re!..)

And the songs/tunes were played over and over until a family member emerged at the door with donations.

The Bhailo rhythms were different. It started with:

”..bhailini aaye angana, (the choir has come to your courtyard)

..guniyo cholo magan (to ask for a dress; guniyo=skirt, cholo=blouse)

..heh aunsi bara, (this day of the New Moon)

..gai ko tihar bhailo!...” (this cow tihar, bhailo!)

And the beat continued...

Saturday, September 26, 2009

The Barbarians

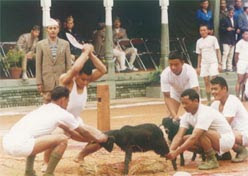

Another interesting aspect of Dashain was the various animal sacrifices offered to goddess Bhavani. The Brahmin hindus mostly preferred to sacrifice a goat, whereas the Newar hindus sacrificed either chicken/duck or buffalo. The ritual of sacrifice was elaborate and often planned days or even weeks in advance. Individual families would spend several days searching for the perfect animal in the livestock market. In our case, the search party involved mostly my grandfather, accompanied by his grandchildren (myself and my cousins), and occasionally by my uncle too. So we would visit the livestock market in Tundikhel (this was the 70s) looking for a young, healthy goat that had no obvious marks (bruises, cuts etc.) on its body and had thick and shiny black fur. Only when black goats were not available we would select a brown or a white goat. I don’t think we ever had to select a goat that was not black. This sometimes meant paying a premium price for the goat, as every family wanted the sacrificial goat to be as perfect as it could be.

While visiting the livestock market was fun, the whole affair of goat selection and the subsequent sacrifice was horrible for the poor animal. Once the selection was determined, my grandfather and my uncle negotiated the price with the seller and this sometimes required a mastery of the art of negotiation. You pretended that you are walking away from the sale looking for another seller, sometimes you argued why the goat was not worth its price by drawing the owner’s attention to the physical defects of the animal. Not that the animal really had a defect, it’s just that you needed something to be critical about in the hopes that the seller would soften a little bit. During Dashain time it was often customary to buy a pair of goats, the young one (Boka in Nepali, male, not neutered) would be sacrificed at the temple, the matured one (Khasi, male, neutered) would be slaughtered at the neighborhood butcher’s shop. The goats were tied with a short rope around their neck, we would hold the rope and let them follow us. If the goat was too stubborn to leave its other companions at the market, one of us got behind it and hit its hind legs with a small stick or with our palm. The journey home would often be very interesting. If taxis were available, we would take the taxi and put the goat in the trunk. But if we had to walk home, this would entail a very careful navigation of the streets through Asan and Chettrapati, which were crowded with people shopping for Dashain. Sometimes the goat would set itself free from our hands and dart across the street, we had to run after it as fast as it could, as losing it meant not only a couple hundred rupees gone down the drain but also initiating the search all over again. Once home, we played with the goats feeding them grass or corn, and teasing and torturing by all means possible. Because we didn’t really have a place for the goat in our house, typically we bought the goats a day or two ahead of the sacrifice. I often wondered what the goats felt when they were separated from their family or companions, and when they had to walk through the busy street and tolerate the humiliation we inflicted upon them. One thing was sure, I did not want to be one of those poor goats, which was raised, and ironically, even loved just to be sacrificed to fulfill our religious practices and beliefs. Never did I question why the goats had to live and die that way, we were simply doing what everybody did in the name of celebrating Dashain.

On the fateful day (the eighth day or Ashtami), my uncle and I would bring the black goat to Shoba Bhagavati temple. The temple organizers always separated worshippers in three lines: male worshippers, female worshipper, and those with sacrificial animals. I have witnessed these sacrifices without any feelings of guilt, emotion or stress. I think I was inhumanely indifferent to the animal. The priest’s aide would grab the goat by its neck with his left hand, the knife on his right hand, his knee holding the lower part of the goat's body lest it sets itself free. He would then pierce the lower neck with the knife and run it across the neck, the blood that squeezed was offered to the goddess. After a while the goat would be silent, decapitated and ready to be put in a jute sack and carried home for butchering and then feasting. All this would occur in the early hours of the day, usually before six in the morning. The sacrifice, it was believed, would bring us happiness, peace and prosperity. At that time I had no doubts it brought us happiness – we would be feasting on delicious goat meat later during the day. About peace, I don’t know, I certainly thought that even the goat knew its fate as soon as it was brought before the goddess, and perhaps it felt an inner peace while accepting its impending fate. The strange thing was the goat never made any fuss (it did not yelp or made any noise) about being sacrificed even when it saw the priest’s aide and his sharp knife still dripping with fresh blood from previous sacrifice.

The following day (ninth day, Navami), we would bring the other goat to the butcher’s shop. If you did not rise up early (just before dawn), you would be so far behind the line that you would have to wait hours until your turn came. For that day the street would be the butcher’s shop, for he would build a makeshift stove on a street corner and place a big open-top pot of boiling water. The slaughter went something like this: the butcher asks his assistant to hold the goat’s horns with each hand, the owner of the goat holds the hind legs with both hands as some owners were too afraid to hold the horns lest the butcher misses his target, the butcher places a block of wood on the ground right below the goat’s neck. Once the goat is positioned, the butcher sprinkles some water on the goats head, if the goat shakes its head it is now auspicious to kill the goat, if it doesn’t, the butcher waits for a while and tries again. Once the goat is ready, the butcher positions himself perpendicular to the goat, brings his crescent-shaped khukuri (traditional Nepali knife made of iron) high above his head and then with one strong downward swing strikes the goat’s neck. The goat is now completely decapitated, the butcher rushes to hold the body and squeezes the blood into a pan. He then starts skinning, gutting, cleaning, cutting, etc. The goat would be ready as meat in less than an hour.

For some reasons, kids in my neighborhood were fascinated to see the killing, on occasions some people would walk around with their big khukuri volunteering to do the killing, sometimes the killer (if he was just a novice) will have to attempt more than once to finish a single job. This macabre affair was celebrated by young and adults alike, all in the name of religion and festival. I guess violence is an innate human character, the beast within us rises on such occasions, affirming our belief that we are the supreme animals, the conquerors. The goat becomes a mute victim, a silent witness to such barbaric acts. I am still puzzled why I and other kids my age (I was around ten years older at that time) were fascinated with such acts of cruelty inflicted upon the goat. Not that I had a violent attitude. The whole episode of goat sacrificing and butchering was somewhat reassuring to me that my fate would be different from that of the poor goat, though I can’t still figure out what was so reassuring about it. The goat was innocent looking, often pitifully tied next to the one that was being slaughtered, its sad eyes pleading for mercy. Silence blanketed the early morning atmosphere, broken only by the occasional crackling noise coming from the burning firewood, the occasional yelp of the goats, the whacking sound of the knife, and the chatter of the few people that were around to witness the cruetly. The silence seemed ungodly, the dawn prophetic.

While visiting the livestock market was fun, the whole affair of goat selection and the subsequent sacrifice was horrible for the poor animal. Once the selection was determined, my grandfather and my uncle negotiated the price with the seller and this sometimes required a mastery of the art of negotiation. You pretended that you are walking away from the sale looking for another seller, sometimes you argued why the goat was not worth its price by drawing the owner’s attention to the physical defects of the animal. Not that the animal really had a defect, it’s just that you needed something to be critical about in the hopes that the seller would soften a little bit. During Dashain time it was often customary to buy a pair of goats, the young one (Boka in Nepali, male, not neutered) would be sacrificed at the temple, the matured one (Khasi, male, neutered) would be slaughtered at the neighborhood butcher’s shop. The goats were tied with a short rope around their neck, we would hold the rope and let them follow us. If the goat was too stubborn to leave its other companions at the market, one of us got behind it and hit its hind legs with a small stick or with our palm. The journey home would often be very interesting. If taxis were available, we would take the taxi and put the goat in the trunk. But if we had to walk home, this would entail a very careful navigation of the streets through Asan and Chettrapati, which were crowded with people shopping for Dashain. Sometimes the goat would set itself free from our hands and dart across the street, we had to run after it as fast as it could, as losing it meant not only a couple hundred rupees gone down the drain but also initiating the search all over again. Once home, we played with the goats feeding them grass or corn, and teasing and torturing by all means possible. Because we didn’t really have a place for the goat in our house, typically we bought the goats a day or two ahead of the sacrifice. I often wondered what the goats felt when they were separated from their family or companions, and when they had to walk through the busy street and tolerate the humiliation we inflicted upon them. One thing was sure, I did not want to be one of those poor goats, which was raised, and ironically, even loved just to be sacrificed to fulfill our religious practices and beliefs. Never did I question why the goats had to live and die that way, we were simply doing what everybody did in the name of celebrating Dashain.

On the fateful day (the eighth day or Ashtami), my uncle and I would bring the black goat to Shoba Bhagavati temple. The temple organizers always separated worshippers in three lines: male worshippers, female worshipper, and those with sacrificial animals. I have witnessed these sacrifices without any feelings of guilt, emotion or stress. I think I was inhumanely indifferent to the animal. The priest’s aide would grab the goat by its neck with his left hand, the knife on his right hand, his knee holding the lower part of the goat's body lest it sets itself free. He would then pierce the lower neck with the knife and run it across the neck, the blood that squeezed was offered to the goddess. After a while the goat would be silent, decapitated and ready to be put in a jute sack and carried home for butchering and then feasting. All this would occur in the early hours of the day, usually before six in the morning. The sacrifice, it was believed, would bring us happiness, peace and prosperity. At that time I had no doubts it brought us happiness – we would be feasting on delicious goat meat later during the day. About peace, I don’t know, I certainly thought that even the goat knew its fate as soon as it was brought before the goddess, and perhaps it felt an inner peace while accepting its impending fate. The strange thing was the goat never made any fuss (it did not yelp or made any noise) about being sacrificed even when it saw the priest’s aide and his sharp knife still dripping with fresh blood from previous sacrifice.

The following day (ninth day, Navami), we would bring the other goat to the butcher’s shop. If you did not rise up early (just before dawn), you would be so far behind the line that you would have to wait hours until your turn came. For that day the street would be the butcher’s shop, for he would build a makeshift stove on a street corner and place a big open-top pot of boiling water. The slaughter went something like this: the butcher asks his assistant to hold the goat’s horns with each hand, the owner of the goat holds the hind legs with both hands as some owners were too afraid to hold the horns lest the butcher misses his target, the butcher places a block of wood on the ground right below the goat’s neck. Once the goat is positioned, the butcher sprinkles some water on the goats head, if the goat shakes its head it is now auspicious to kill the goat, if it doesn’t, the butcher waits for a while and tries again. Once the goat is ready, the butcher positions himself perpendicular to the goat, brings his crescent-shaped khukuri (traditional Nepali knife made of iron) high above his head and then with one strong downward swing strikes the goat’s neck. The goat is now completely decapitated, the butcher rushes to hold the body and squeezes the blood into a pan. He then starts skinning, gutting, cleaning, cutting, etc. The goat would be ready as meat in less than an hour.

For some reasons, kids in my neighborhood were fascinated to see the killing, on occasions some people would walk around with their big khukuri volunteering to do the killing, sometimes the killer (if he was just a novice) will have to attempt more than once to finish a single job. This macabre affair was celebrated by young and adults alike, all in the name of religion and festival. I guess violence is an innate human character, the beast within us rises on such occasions, affirming our belief that we are the supreme animals, the conquerors. The goat becomes a mute victim, a silent witness to such barbaric acts. I am still puzzled why I and other kids my age (I was around ten years older at that time) were fascinated with such acts of cruelty inflicted upon the goat. Not that I had a violent attitude. The whole episode of goat sacrificing and butchering was somewhat reassuring to me that my fate would be different from that of the poor goat, though I can’t still figure out what was so reassuring about it. The goat was innocent looking, often pitifully tied next to the one that was being slaughtered, its sad eyes pleading for mercy. Silence blanketed the early morning atmosphere, broken only by the occasional crackling noise coming from the burning firewood, the occasional yelp of the goats, the whacking sound of the knife, and the chatter of the few people that were around to witness the cruetly. The silence seemed ungodly, the dawn prophetic.

Sunday, September 13, 2009

Let's Go Fly a Kite

The nice thing about the start of Dashain was that it also coincided with the kite season. Now-a-days flying a kite in Kathmandu is not as common as it used to be, this splendid sport used to be the favorite pasttime of kids and adults alike in the 70s. One could see hundreds of kites on Kathmandu’s sky gliding elegantly or fighting a fierce battle with one another and pulling all the tricks it could to bring someone else down. I suppose the sport fell victim to growing popularity of technology-driven entertainment and ATARI and other games of the late 80s and 90s. Kite flying, marbles (guccha), tash (cards), and other sports like tel kasa (game that involves giving a chase), aas paas (hide and seek) began to disappear slowly and if you ask young kids these days if they played any such games I bet with the exception of kite flying they would not have a clue how these games are played.

Anyway, flying a kite gave us tremendous joy, just like how the author of The Kite Runner describes in the book. We had to go to Ason Tole to buy the best kites, the kites came in a dazzle of colors. The kite flying apparatus consisted of the kite (made of paper) itself, the wooden reel with two spools on either side which you had to hold in your hands to manipulate the kite as it is airborne. Miles and miles of string were rolled onto the reel. The string was often fortified with homemade manja, a mixture of crushed glass and thick adhesive. The strength of the string depended on the quality of the mixture. I was not good at flying kite; I tried several times but never could master the art. Some of my friends were excellent kite flyers so I used to visit them in their house. We would go to the roof and spent hours flying the kite and engaging with others on kite fights. Depending on wind conditions and wind directions, we positioned our kites in a way that it would reach very high up in the sky. The kite would slowly rise up, sometimes dancing like a beautiful ballerina, and at other times furious as a dragon warrior. We always made sure that before we engaged in a fight we had ample time to enjoy the high flying and the theatrics in the sky.

There were different types of kites in the sky, some were big some small. Some had “two color” pattern, some were three or four colors, most kites we flew were square shaped. Most Nepali kites were of the Malay variety: a two sticker without a tail, both sticks of equal length crossed and tied with center of one at a spot one-seventh the distance from the top of the other; a bridle attached to the kite had two legs, one from the top of the diamond and the other from the lowest point, meeting a little below the crossing of the sticks; a string pulled tight across the back of the cross stick bowed the surface making the kite self-balancing. The Nepali kites were mostly made of lokta hand-made paper. Because the kites did not come with a tail attached, sometimes, we would make the tails ourselves. It was a pure joy to see the kite twisting and turning its tail as it became airborne and flew higher and higher. The sight of the colorful kites against the blue sky and the sounds (of yells, hoots, cheers, laughs, and occasional curses) made kite flying a memorable affair.

The kite fights were intense, the successful fighters were those who could anticipate the moves of their rivals, and of course who had championed the art and whose strings were the strongest. The manja fortified strings could strike a terror on unsuspecting kites. On any given day, you could see several kite duels in the sky and even if you were just a spectator on the roof or on the street below you would cast an intense gaze toward the sky, your eyes sparkled with the thrill, your jaws shut tight due to the intensity, and your heart pounding at the prospect of catching the losing kite. You would stay focused on one of the many duels and would anticipate the right timing of one of the kites being cut loose and then run towards the falling kite to catch it. There were times when I was rewarded but there were also times when the kite just tore apart due to the intense shuffle amongst the kite runners. As a rule, if you were the first one to catch it other runners would let you have the kite, but it was well understood by kite runners that the moment you run toward the falling kite you were a gladiator racing against others who would come from different directions trying to be the first one to arrive. The race would almost always determine that there were no clear winners and a fist fight would ensue. It was one of the main reasons why I tried not to take part in the race; as if the fate of the falling kite was predetermined. On a few occasions, when my friends or I were lucky to be the winner of a bruised or battered kite, we would spent hours trying to resurrect it and let it fly one more time in the hopes that it might be able to challenge the victor. And when it did, the kite became our inspiration, a symbol of hope to restore lost glory, and a way to redeem ourselves. The next few days would be spent on telling the heroic tale to our friends in the neighborhood.

Anyway, flying a kite gave us tremendous joy, just like how the author of The Kite Runner describes in the book. We had to go to Ason Tole to buy the best kites, the kites came in a dazzle of colors. The kite flying apparatus consisted of the kite (made of paper) itself, the wooden reel with two spools on either side which you had to hold in your hands to manipulate the kite as it is airborne. Miles and miles of string were rolled onto the reel. The string was often fortified with homemade manja, a mixture of crushed glass and thick adhesive. The strength of the string depended on the quality of the mixture. I was not good at flying kite; I tried several times but never could master the art. Some of my friends were excellent kite flyers so I used to visit them in their house. We would go to the roof and spent hours flying the kite and engaging with others on kite fights. Depending on wind conditions and wind directions, we positioned our kites in a way that it would reach very high up in the sky. The kite would slowly rise up, sometimes dancing like a beautiful ballerina, and at other times furious as a dragon warrior. We always made sure that before we engaged in a fight we had ample time to enjoy the high flying and the theatrics in the sky.

There were different types of kites in the sky, some were big some small. Some had “two color” pattern, some were three or four colors, most kites we flew were square shaped. Most Nepali kites were of the Malay variety: a two sticker without a tail, both sticks of equal length crossed and tied with center of one at a spot one-seventh the distance from the top of the other; a bridle attached to the kite had two legs, one from the top of the diamond and the other from the lowest point, meeting a little below the crossing of the sticks; a string pulled tight across the back of the cross stick bowed the surface making the kite self-balancing. The Nepali kites were mostly made of lokta hand-made paper. Because the kites did not come with a tail attached, sometimes, we would make the tails ourselves. It was a pure joy to see the kite twisting and turning its tail as it became airborne and flew higher and higher. The sight of the colorful kites against the blue sky and the sounds (of yells, hoots, cheers, laughs, and occasional curses) made kite flying a memorable affair.

The kite fights were intense, the successful fighters were those who could anticipate the moves of their rivals, and of course who had championed the art and whose strings were the strongest. The manja fortified strings could strike a terror on unsuspecting kites. On any given day, you could see several kite duels in the sky and even if you were just a spectator on the roof or on the street below you would cast an intense gaze toward the sky, your eyes sparkled with the thrill, your jaws shut tight due to the intensity, and your heart pounding at the prospect of catching the losing kite. You would stay focused on one of the many duels and would anticipate the right timing of one of the kites being cut loose and then run towards the falling kite to catch it. There were times when I was rewarded but there were also times when the kite just tore apart due to the intense shuffle amongst the kite runners. As a rule, if you were the first one to catch it other runners would let you have the kite, but it was well understood by kite runners that the moment you run toward the falling kite you were a gladiator racing against others who would come from different directions trying to be the first one to arrive. The race would almost always determine that there were no clear winners and a fist fight would ensue. It was one of the main reasons why I tried not to take part in the race; as if the fate of the falling kite was predetermined. On a few occasions, when my friends or I were lucky to be the winner of a bruised or battered kite, we would spent hours trying to resurrect it and let it fly one more time in the hopes that it might be able to challenge the victor. And when it did, the kite became our inspiration, a symbol of hope to restore lost glory, and a way to redeem ourselves. The next few days would be spent on telling the heroic tale to our friends in the neighborhood.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)