A couple of days ago, I had the opportunity to visit Shimla in India to attend a conference. I had heard about Shimla since my childhood days (one of my aunts had lived there during the 60s). The movie “Aradhana” which I mentioned in my previous posting, was filmed there including picturising the famous song “Mere sapno ki rani..”. Shimla turned out to be a very charming mountain city. The Brits had chosen it as a place to escape from the scorching summer in New Delhi or Calcutta (the capital city during British Raj), so they developed it as a “hill station”. The colonial imprint is everywhere – the road and rail infrastructure, the buildings (tudor and neo-gothic architecture), street names, names of government buildings etc. One of the longest narrow gauge railway in India brings tourists to Shimla from Kalka. The city today is the state capital of Himachal Pradesh, and as such has grown considerably because of employment prospects, tourism and other entrepreneurial opportunities. I found it to be a very clean city, its people very friendly and its culture similar to those found in the highlands of Nepal. Indeed, the Gurkha empire in its prime had extended its power to these regions, and I was told, their descendants still live there. On the streets, I heard people talking in Nepali and other local dialouges which sounded very much like the languages spoken in the far western mountain regions of Nepal.

The main market center in Shimla is anchored by a historic church located at an altitude of 7200 ft. I went inside the church, and read some of the plaques posted there describing the early pioneers of Shimla, for example, the first British principal of the convent school. Two life size statues of Mahatma Gandhi and Indira Gandhi were nearby. Looking across the city and over in the northerly direction, you could see the snow-capped mountains. Shimla has the atmosphere of a major city tucked high up on the mountains, its little charms include the “Mall” a pedestrian-only street that stretches from the State Parliament building and through the main streets lined with shops enticing tourists to buy local made textiles, general consumer goods, restaurants (yes, Chinese and Mexican too!), banks, western union, etc. I was delighted to see so many people walking, chatting, and just milling around and basking in the afternoon sun. There was something warm about the place and the people, a welcoming environment, which you don’t feel when visiting other big cities whether in India or overseas. I felt I was in a familiar surrounding and decided right there that should an opportunity come in the future I would return to this place again and expore it some more. The snowcapped mountains were inviting me, and I imagined myself someday on a drive or trekking tour to the land of Leh in Laddakh, not very far away from Shimla.

Saturday, December 5, 2009

"The Queen of my dreams..."

Speaking of music and songs, I like to harken back to the late 60s and early 70s. Growing up, I was fascinated by Bollywood movies, who wasn’t back then? They were the only forms of entertainment during those days, and in my grandfather I found one of the biggest fans of Bollywood movies. Every movie he watched, I was with him. I cannot remember some of my earliest movies but I have vague recollections of songs from those movies, for example, “Hum Kale hain to kya huwa dilwale hain..” (I don’t care I am dark-skinned, I have a generous heart) from the movie “Balak”, and “Yeh nargise mastana! basa itni batade tu..” (Hey beautiful! just tell me…) from the blockbuster “Aarju”. Rajendra Kumar, the hero of Aarju was famous and I wanted my mom to part my hair just like Rajendra Kumar’s. I must have been five or six years old. I could sing the songs from these movies and I quickly became the entertainer in my family. There wasn’t a time when I wasn’t humming some tunes from the latest flick. Then in 1969 “Aaradhana” was released, the movie gave rise to the phenomenon “Rajesh Khanna”, who became the first ever Bollywood superstar. He was a romantic hero and sang “Mere sapnoki rani kab aayegi tu..” (The queen of my dreams when will you come to me..”, which instantly became the number one song of the year and declared the supremacy of Kishore Kumar in Hindi music scene. While Kishore had been singing Hindi songs for several years, he played second fiddle to Mohammed Rafi who was hugely popular. 1969 was the beginning of the rise of Kishore Kumar and the declining popularity of Rafi. I was immediately struck by Kishore’s style of singing, his guttural voice and easy manners. I became his fan and to this day, I remain his most loyal fan.

So I started singing “Mere sapno ki rani..” and other Kishore songs. I could sing it well and my talent was quickly recognized at home, in the neighborhood, and at school. I was an eight year old kid, I did not have any inhibitions when it came to singing. If somebody asked me to sing, I would start right away. I don’t know how the school principal found out that I could sing, so when I was in Grade 5 I was asked to sing during school functions. I must have sang well for I was now a fixture at the school’s cultural events. I did not know how to play instruments, something that I would regret later, but I could memorize full verses and then render the songs in a typical Kishore style. Singing led to watching movies, and movies to songs. Some of the most memorable times during that period was the day Crown Prince Dipendra was born. My neighbor Purna Dai took me from home, brought me with him to the ward office (municipal office), which was just next doors from ours, handed me the loudspeaker, have me sit in one of the chairs in the office and instructed me to sing whatever I could and for as long as I could. It was more like the people in my neighborhood wanted to express our happiness on that joyous occasion. I don’t remember how long I sang, but it sure felt like a long day, I must have been their singing non-stop for two-three hours. It was up to me to sing whatever I desired, and that meant singing the ones I knew very well, but also those which I knew only a short verse or so. I sure felt that my neighbors had recognized my talent. Perhaps I was chosen not because I was just a small kid, but I sure had the energy, enthusiasm, the voice and the patience that was demanded of me. Anyway, my rendering of Kishore Kumar’s romantic songs made me a local hero of sorts. From that day onward, everybody in my neighborhood knew me (I was Krishna Baje’s Nati – or my grandfather Krishna’s grandson). One of my friends continues to tease me with the song “Mere sapno ki rani…” whenever we meet.

So I started singing “Mere sapno ki rani..” and other Kishore songs. I could sing it well and my talent was quickly recognized at home, in the neighborhood, and at school. I was an eight year old kid, I did not have any inhibitions when it came to singing. If somebody asked me to sing, I would start right away. I don’t know how the school principal found out that I could sing, so when I was in Grade 5 I was asked to sing during school functions. I must have sang well for I was now a fixture at the school’s cultural events. I did not know how to play instruments, something that I would regret later, but I could memorize full verses and then render the songs in a typical Kishore style. Singing led to watching movies, and movies to songs. Some of the most memorable times during that period was the day Crown Prince Dipendra was born. My neighbor Purna Dai took me from home, brought me with him to the ward office (municipal office), which was just next doors from ours, handed me the loudspeaker, have me sit in one of the chairs in the office and instructed me to sing whatever I could and for as long as I could. It was more like the people in my neighborhood wanted to express our happiness on that joyous occasion. I don’t remember how long I sang, but it sure felt like a long day, I must have been their singing non-stop for two-three hours. It was up to me to sing whatever I desired, and that meant singing the ones I knew very well, but also those which I knew only a short verse or so. I sure felt that my neighbors had recognized my talent. Perhaps I was chosen not because I was just a small kid, but I sure had the energy, enthusiasm, the voice and the patience that was demanded of me. Anyway, my rendering of Kishore Kumar’s romantic songs made me a local hero of sorts. From that day onward, everybody in my neighborhood knew me (I was Krishna Baje’s Nati – or my grandfather Krishna’s grandson). One of my friends continues to tease me with the song “Mere sapno ki rani…” whenever we meet.

Sunday, October 4, 2009

City of Lights

Ok, now that Dashain is over, it’s time to talk about another biggest festival of the year – Tihar. While Dashain is considered as the festival when we eat lots and lots of meat, Tihar is when we eat lots and lots of sweets, all home made. Tihar, or its more formal name Deepawali, is a festival of lights. For three days, the city of Kathmandu turns into city of lights. Every doors and windows are lined with flickering candles and/or oil lamps. Set against the soft darkness of the Fall season, the whole city comes to life as if gods have descended upon it to rejoice and celebrate with the mortal beings. Tihar is very different from Dashain in that it does not involved ritual killings that I described in my previous post. Celebrated for five days, Tihar begins with celebrating the life of a crow – the crow, or Kag in Nepali – according to the Hindu mythology, the cawing of a crow symbolizes sadness or grief, so on the day of Kag Tihar people in Kathmandu try to attract the crow to their balcony or the roof by placing offerings of food. Interestingly, the Nepalese also believe that the cawing of a crow on your rooftop means a guest is likely to pay a visit to your house – there is no shortage of guests at your home during Tihar. Kag Tihar is followed by Kukur (dog) Tihar – the dog is considered a messenger of the god of death Yamaraj. According to the Hindu mythology, the dog escorts you to Yamraj’s gate and tries to guide and protect you from the perils of the journey that takes you to the Yamaraj. On this day, you will see dogs (even stray ones) pampered with sweets, and frolicking in the neighborhood wearing marigold garlands around their necks and red tika on their foreheads. Even the nasty dogs are shown a level of affection not usually common among most Kathmanduities when it comes to stray dogs. To everyone’s surprise the dogs do not engage in street brawls on that day, as if they are also in the mood to rejoice, celebrate and at peace with each other acknowledging the right to co-exist. The atmosphere on the streets of Kathmandu seems serene, harmonious and joyful.

The third day of Tihar is Gai (cow) Puja or Laxmi Puja. The mother cow is the holiest of all animals in Hindu mythology, the giver of precious milk to nourish our bodies, the manure to fertilize the earth, and in rural households to purify homes and courtyards with its manure. The cow symbolizes the spirit of kindness, and of motherly love. The cow is worshipped (tika on her forehead, marigold garland around her neck) and offered fruits and homemade sweets. The cow is also a manifestation of the goddess of wealth (Laxmi). In rural Nepal the number of milk giving cows in your livestock shed is often the barometer of your prosperity in the village. As most travelers to Nepal know, the cow is a mighty force even on the most congested streets of Kathmandu where she roams free, unobstructed, and with little care for the imminent dangers from cars, motorbikes, rickshaws and people. Anytime I am on the streets of Kathmandu, for example, on the highly congested section between Indrachowk and Kamalachhi, the sight of a cow and her carefree spirit instills in me a true sense of freedom, a realization that is most unrealizable, imagination that is anything but impossible. So we celebrate Gai Tihar with unflinching spirit and with a care that attains its highest level on that day. We watch her move around the neighborhood with grace, kindness, humility and pure freedom. Families engage in elaborate decorations of their entrances with small prints of Laxmi’s feet, hoping that she visits the house softly at night and brings prosperity to the families. On the fourth day, we celebrate Gobardhan Puja, or Goru (ox) puja. This is the day when farmers worship the mighty Goru, the one that ploughs the earth with its sheer strength and determination. Farmers have special affinity with the Goru, not only it is Lord Pashupati’s carrier, it is also the principal source of labor without which many farmers in the Nepalese hills and terai cannot till their lands.

On the fifth and the final day of Tihar, Bhai Tika is celebrated. Brothers and sisters throughout Nepal reunite and put tika on each other, sisters pray for their brothers’ safety, brothers promise to protect their sisters. Those without a brother or a sister visit the temple in Rani Pokhari, which is opened for public visit only on that day during the whole year. In my family the ritual of Bhaitika takes more than two or three hours. You see, I have four sisters, the tika ceremony is very elaborate, completed in stages starting with putting oil on my head the night before and culminating with the exchange of fruits and sweets the next day. The family ritual on the day of Bhaitika involves the sisters circumnavigating the brother (seated on the ground, legs crossed) and drawing a line of oil and water brushed by fresh dubo (a small clump of fresh grass neatly tied toether) around him, demarcating a boundary which no forces of evil can penetrate. Thereafter, they take turns in putting the multicolored tika on the forehead, the tika is put in a vertical row of red, blue, purple, yellow, green, and black colors. They put garlands of dubo, purple colored makhamali (Globe amaranth / Gomphrena globosa) and marigold flowers around the brother’s neck, give him fruits, homemade sweets (sel, anarsa, khajuri) and masala (dry spices - a mix of almonds, coconut, plum, cashew, etc). In return, the brother puts tika in similar fashion on the foreheads of his sister, starting from the eldest and to the youngest, gives them fruits, sweets and money. The ceremony ends with a family feast.

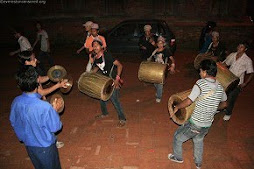

On the third and the fourth day, the night comes alive. This is the day when children and adults alike band together to form singing groups and visit different homes to sing Deusi (third day) and Bhailo (fourth day) in return for money and/or other offerings. The night is brightly lit with candles and oil lamps, there is music in the air, fireworks sparkle the night sky with radiant colors, children come out on the streets beautifully dressed, and peace and harmony litter the streets of Kathmandu. I participated in these events with almost a missionary zeal. We would plan singing days in advance, preparing a list of homes to visit, and in some cases sending them an advance notice that we would be coming to sing at their house. We would plan our lineup of songs (Deusi or Bhailo were the main songs, but we would also sing other popular Nepali folk and Bollywood songs), instruments to be played and determine who would be playing what. For Bollywood songs, I would be one of the lead vocalists. We would start visiting homes at seven in the evening or as soon as it is dark, working through our neighborhood and then moving on further. Depending on the size of the group (sometimes it would be around 6-7, but mostly it was more than 10 in the group), we would collect various amounts of money during the two nights. Often, we sang and played until mid-night. The money would be spent on some group activities, for example, a picnic at the outskirts of Kathmandu, planned in the days to come. One year, we had more than 20 in the group so we had to rent a minivan to go around, for example, we sang at the western entrance (Keshar Mahal) of the Royal Palace (we had to send a notice several days in advance) and at the Prime Ministers’ official residence in Baluwatar. The beauty of the Deusi song was that as long as you followed its rhythm you could sing almost about anything you wanted, which usually meant singing in praise of the family you were visiting, but also singing about the difficulty faced along our way to the house, our impatience with the time it has taken for the family to give their donations, etc. which were smartly built into our tunes. Our Deusi song went something like this:

Heh…jhilimili jhilla, deusi re!…(glitter galore, deusi re!)

Heh…tato roti milla, deusi re!…(hot bread (we shall receive) deusi re!)

Heh…rato mato, deusi re!…(red mud, deusi re!..)

Heh…chiplo bato, deusi re!…(slippery path, deusi re!…)

Heh…aayon hami, deusi re!… (we came, deusi re!..)

Heh…deusi gauna, deusi re!… (to sing deusi, deusi re!..)

Heh…yo ghar ko rani, deusi re!…(this home’s queen, deusi re!..)

Heh…Kasto ramro bani, deusi re!…(how nice is she, deusi re!..)

And the songs/tunes were played over and over until a family member emerged at the door with donations.

The Bhailo rhythms were different. It started with:

”..bhailini aaye angana, (the choir has come to your courtyard)

..guniyo cholo magan (to ask for a dress; guniyo=skirt, cholo=blouse)

..heh aunsi bara, (this day of the New Moon)

..gai ko tihar bhailo!...” (this cow tihar, bhailo!)

And the beat continued...

The third day of Tihar is Gai (cow) Puja or Laxmi Puja. The mother cow is the holiest of all animals in Hindu mythology, the giver of precious milk to nourish our bodies, the manure to fertilize the earth, and in rural households to purify homes and courtyards with its manure. The cow symbolizes the spirit of kindness, and of motherly love. The cow is worshipped (tika on her forehead, marigold garland around her neck) and offered fruits and homemade sweets. The cow is also a manifestation of the goddess of wealth (Laxmi). In rural Nepal the number of milk giving cows in your livestock shed is often the barometer of your prosperity in the village. As most travelers to Nepal know, the cow is a mighty force even on the most congested streets of Kathmandu where she roams free, unobstructed, and with little care for the imminent dangers from cars, motorbikes, rickshaws and people. Anytime I am on the streets of Kathmandu, for example, on the highly congested section between Indrachowk and Kamalachhi, the sight of a cow and her carefree spirit instills in me a true sense of freedom, a realization that is most unrealizable, imagination that is anything but impossible. So we celebrate Gai Tihar with unflinching spirit and with a care that attains its highest level on that day. We watch her move around the neighborhood with grace, kindness, humility and pure freedom. Families engage in elaborate decorations of their entrances with small prints of Laxmi’s feet, hoping that she visits the house softly at night and brings prosperity to the families. On the fourth day, we celebrate Gobardhan Puja, or Goru (ox) puja. This is the day when farmers worship the mighty Goru, the one that ploughs the earth with its sheer strength and determination. Farmers have special affinity with the Goru, not only it is Lord Pashupati’s carrier, it is also the principal source of labor without which many farmers in the Nepalese hills and terai cannot till their lands.

On the fifth and the final day of Tihar, Bhai Tika is celebrated. Brothers and sisters throughout Nepal reunite and put tika on each other, sisters pray for their brothers’ safety, brothers promise to protect their sisters. Those without a brother or a sister visit the temple in Rani Pokhari, which is opened for public visit only on that day during the whole year. In my family the ritual of Bhaitika takes more than two or three hours. You see, I have four sisters, the tika ceremony is very elaborate, completed in stages starting with putting oil on my head the night before and culminating with the exchange of fruits and sweets the next day. The family ritual on the day of Bhaitika involves the sisters circumnavigating the brother (seated on the ground, legs crossed) and drawing a line of oil and water brushed by fresh dubo (a small clump of fresh grass neatly tied toether) around him, demarcating a boundary which no forces of evil can penetrate. Thereafter, they take turns in putting the multicolored tika on the forehead, the tika is put in a vertical row of red, blue, purple, yellow, green, and black colors. They put garlands of dubo, purple colored makhamali (Globe amaranth / Gomphrena globosa) and marigold flowers around the brother’s neck, give him fruits, homemade sweets (sel, anarsa, khajuri) and masala (dry spices - a mix of almonds, coconut, plum, cashew, etc). In return, the brother puts tika in similar fashion on the foreheads of his sister, starting from the eldest and to the youngest, gives them fruits, sweets and money. The ceremony ends with a family feast.

On the third and the fourth day, the night comes alive. This is the day when children and adults alike band together to form singing groups and visit different homes to sing Deusi (third day) and Bhailo (fourth day) in return for money and/or other offerings. The night is brightly lit with candles and oil lamps, there is music in the air, fireworks sparkle the night sky with radiant colors, children come out on the streets beautifully dressed, and peace and harmony litter the streets of Kathmandu. I participated in these events with almost a missionary zeal. We would plan singing days in advance, preparing a list of homes to visit, and in some cases sending them an advance notice that we would be coming to sing at their house. We would plan our lineup of songs (Deusi or Bhailo were the main songs, but we would also sing other popular Nepali folk and Bollywood songs), instruments to be played and determine who would be playing what. For Bollywood songs, I would be one of the lead vocalists. We would start visiting homes at seven in the evening or as soon as it is dark, working through our neighborhood and then moving on further. Depending on the size of the group (sometimes it would be around 6-7, but mostly it was more than 10 in the group), we would collect various amounts of money during the two nights. Often, we sang and played until mid-night. The money would be spent on some group activities, for example, a picnic at the outskirts of Kathmandu, planned in the days to come. One year, we had more than 20 in the group so we had to rent a minivan to go around, for example, we sang at the western entrance (Keshar Mahal) of the Royal Palace (we had to send a notice several days in advance) and at the Prime Ministers’ official residence in Baluwatar. The beauty of the Deusi song was that as long as you followed its rhythm you could sing almost about anything you wanted, which usually meant singing in praise of the family you were visiting, but also singing about the difficulty faced along our way to the house, our impatience with the time it has taken for the family to give their donations, etc. which were smartly built into our tunes. Our Deusi song went something like this:

Heh…jhilimili jhilla, deusi re!…(glitter galore, deusi re!)

Heh…tato roti milla, deusi re!…(hot bread (we shall receive) deusi re!)

Heh…rato mato, deusi re!…(red mud, deusi re!..)

Heh…chiplo bato, deusi re!…(slippery path, deusi re!…)

Heh…aayon hami, deusi re!… (we came, deusi re!..)

Heh…deusi gauna, deusi re!… (to sing deusi, deusi re!..)

Heh…yo ghar ko rani, deusi re!…(this home’s queen, deusi re!..)

Heh…Kasto ramro bani, deusi re!…(how nice is she, deusi re!..)

And the songs/tunes were played over and over until a family member emerged at the door with donations.

The Bhailo rhythms were different. It started with:

”..bhailini aaye angana, (the choir has come to your courtyard)

..guniyo cholo magan (to ask for a dress; guniyo=skirt, cholo=blouse)

..heh aunsi bara, (this day of the New Moon)

..gai ko tihar bhailo!...” (this cow tihar, bhailo!)

And the beat continued...

Saturday, September 26, 2009

The Barbarians

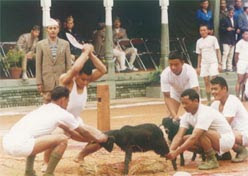

Another interesting aspect of Dashain was the various animal sacrifices offered to goddess Bhavani. The Brahmin hindus mostly preferred to sacrifice a goat, whereas the Newar hindus sacrificed either chicken/duck or buffalo. The ritual of sacrifice was elaborate and often planned days or even weeks in advance. Individual families would spend several days searching for the perfect animal in the livestock market. In our case, the search party involved mostly my grandfather, accompanied by his grandchildren (myself and my cousins), and occasionally by my uncle too. So we would visit the livestock market in Tundikhel (this was the 70s) looking for a young, healthy goat that had no obvious marks (bruises, cuts etc.) on its body and had thick and shiny black fur. Only when black goats were not available we would select a brown or a white goat. I don’t think we ever had to select a goat that was not black. This sometimes meant paying a premium price for the goat, as every family wanted the sacrificial goat to be as perfect as it could be.

While visiting the livestock market was fun, the whole affair of goat selection and the subsequent sacrifice was horrible for the poor animal. Once the selection was determined, my grandfather and my uncle negotiated the price with the seller and this sometimes required a mastery of the art of negotiation. You pretended that you are walking away from the sale looking for another seller, sometimes you argued why the goat was not worth its price by drawing the owner’s attention to the physical defects of the animal. Not that the animal really had a defect, it’s just that you needed something to be critical about in the hopes that the seller would soften a little bit. During Dashain time it was often customary to buy a pair of goats, the young one (Boka in Nepali, male, not neutered) would be sacrificed at the temple, the matured one (Khasi, male, neutered) would be slaughtered at the neighborhood butcher’s shop. The goats were tied with a short rope around their neck, we would hold the rope and let them follow us. If the goat was too stubborn to leave its other companions at the market, one of us got behind it and hit its hind legs with a small stick or with our palm. The journey home would often be very interesting. If taxis were available, we would take the taxi and put the goat in the trunk. But if we had to walk home, this would entail a very careful navigation of the streets through Asan and Chettrapati, which were crowded with people shopping for Dashain. Sometimes the goat would set itself free from our hands and dart across the street, we had to run after it as fast as it could, as losing it meant not only a couple hundred rupees gone down the drain but also initiating the search all over again. Once home, we played with the goats feeding them grass or corn, and teasing and torturing by all means possible. Because we didn’t really have a place for the goat in our house, typically we bought the goats a day or two ahead of the sacrifice. I often wondered what the goats felt when they were separated from their family or companions, and when they had to walk through the busy street and tolerate the humiliation we inflicted upon them. One thing was sure, I did not want to be one of those poor goats, which was raised, and ironically, even loved just to be sacrificed to fulfill our religious practices and beliefs. Never did I question why the goats had to live and die that way, we were simply doing what everybody did in the name of celebrating Dashain.

On the fateful day (the eighth day or Ashtami), my uncle and I would bring the black goat to Shoba Bhagavati temple. The temple organizers always separated worshippers in three lines: male worshippers, female worshipper, and those with sacrificial animals. I have witnessed these sacrifices without any feelings of guilt, emotion or stress. I think I was inhumanely indifferent to the animal. The priest’s aide would grab the goat by its neck with his left hand, the knife on his right hand, his knee holding the lower part of the goat's body lest it sets itself free. He would then pierce the lower neck with the knife and run it across the neck, the blood that squeezed was offered to the goddess. After a while the goat would be silent, decapitated and ready to be put in a jute sack and carried home for butchering and then feasting. All this would occur in the early hours of the day, usually before six in the morning. The sacrifice, it was believed, would bring us happiness, peace and prosperity. At that time I had no doubts it brought us happiness – we would be feasting on delicious goat meat later during the day. About peace, I don’t know, I certainly thought that even the goat knew its fate as soon as it was brought before the goddess, and perhaps it felt an inner peace while accepting its impending fate. The strange thing was the goat never made any fuss (it did not yelp or made any noise) about being sacrificed even when it saw the priest’s aide and his sharp knife still dripping with fresh blood from previous sacrifice.

The following day (ninth day, Navami), we would bring the other goat to the butcher’s shop. If you did not rise up early (just before dawn), you would be so far behind the line that you would have to wait hours until your turn came. For that day the street would be the butcher’s shop, for he would build a makeshift stove on a street corner and place a big open-top pot of boiling water. The slaughter went something like this: the butcher asks his assistant to hold the goat’s horns with each hand, the owner of the goat holds the hind legs with both hands as some owners were too afraid to hold the horns lest the butcher misses his target, the butcher places a block of wood on the ground right below the goat’s neck. Once the goat is positioned, the butcher sprinkles some water on the goats head, if the goat shakes its head it is now auspicious to kill the goat, if it doesn’t, the butcher waits for a while and tries again. Once the goat is ready, the butcher positions himself perpendicular to the goat, brings his crescent-shaped khukuri (traditional Nepali knife made of iron) high above his head and then with one strong downward swing strikes the goat’s neck. The goat is now completely decapitated, the butcher rushes to hold the body and squeezes the blood into a pan. He then starts skinning, gutting, cleaning, cutting, etc. The goat would be ready as meat in less than an hour.

For some reasons, kids in my neighborhood were fascinated to see the killing, on occasions some people would walk around with their big khukuri volunteering to do the killing, sometimes the killer (if he was just a novice) will have to attempt more than once to finish a single job. This macabre affair was celebrated by young and adults alike, all in the name of religion and festival. I guess violence is an innate human character, the beast within us rises on such occasions, affirming our belief that we are the supreme animals, the conquerors. The goat becomes a mute victim, a silent witness to such barbaric acts. I am still puzzled why I and other kids my age (I was around ten years older at that time) were fascinated with such acts of cruelty inflicted upon the goat. Not that I had a violent attitude. The whole episode of goat sacrificing and butchering was somewhat reassuring to me that my fate would be different from that of the poor goat, though I can’t still figure out what was so reassuring about it. The goat was innocent looking, often pitifully tied next to the one that was being slaughtered, its sad eyes pleading for mercy. Silence blanketed the early morning atmosphere, broken only by the occasional crackling noise coming from the burning firewood, the occasional yelp of the goats, the whacking sound of the knife, and the chatter of the few people that were around to witness the cruetly. The silence seemed ungodly, the dawn prophetic.

While visiting the livestock market was fun, the whole affair of goat selection and the subsequent sacrifice was horrible for the poor animal. Once the selection was determined, my grandfather and my uncle negotiated the price with the seller and this sometimes required a mastery of the art of negotiation. You pretended that you are walking away from the sale looking for another seller, sometimes you argued why the goat was not worth its price by drawing the owner’s attention to the physical defects of the animal. Not that the animal really had a defect, it’s just that you needed something to be critical about in the hopes that the seller would soften a little bit. During Dashain time it was often customary to buy a pair of goats, the young one (Boka in Nepali, male, not neutered) would be sacrificed at the temple, the matured one (Khasi, male, neutered) would be slaughtered at the neighborhood butcher’s shop. The goats were tied with a short rope around their neck, we would hold the rope and let them follow us. If the goat was too stubborn to leave its other companions at the market, one of us got behind it and hit its hind legs with a small stick or with our palm. The journey home would often be very interesting. If taxis were available, we would take the taxi and put the goat in the trunk. But if we had to walk home, this would entail a very careful navigation of the streets through Asan and Chettrapati, which were crowded with people shopping for Dashain. Sometimes the goat would set itself free from our hands and dart across the street, we had to run after it as fast as it could, as losing it meant not only a couple hundred rupees gone down the drain but also initiating the search all over again. Once home, we played with the goats feeding them grass or corn, and teasing and torturing by all means possible. Because we didn’t really have a place for the goat in our house, typically we bought the goats a day or two ahead of the sacrifice. I often wondered what the goats felt when they were separated from their family or companions, and when they had to walk through the busy street and tolerate the humiliation we inflicted upon them. One thing was sure, I did not want to be one of those poor goats, which was raised, and ironically, even loved just to be sacrificed to fulfill our religious practices and beliefs. Never did I question why the goats had to live and die that way, we were simply doing what everybody did in the name of celebrating Dashain.

On the fateful day (the eighth day or Ashtami), my uncle and I would bring the black goat to Shoba Bhagavati temple. The temple organizers always separated worshippers in three lines: male worshippers, female worshipper, and those with sacrificial animals. I have witnessed these sacrifices without any feelings of guilt, emotion or stress. I think I was inhumanely indifferent to the animal. The priest’s aide would grab the goat by its neck with his left hand, the knife on his right hand, his knee holding the lower part of the goat's body lest it sets itself free. He would then pierce the lower neck with the knife and run it across the neck, the blood that squeezed was offered to the goddess. After a while the goat would be silent, decapitated and ready to be put in a jute sack and carried home for butchering and then feasting. All this would occur in the early hours of the day, usually before six in the morning. The sacrifice, it was believed, would bring us happiness, peace and prosperity. At that time I had no doubts it brought us happiness – we would be feasting on delicious goat meat later during the day. About peace, I don’t know, I certainly thought that even the goat knew its fate as soon as it was brought before the goddess, and perhaps it felt an inner peace while accepting its impending fate. The strange thing was the goat never made any fuss (it did not yelp or made any noise) about being sacrificed even when it saw the priest’s aide and his sharp knife still dripping with fresh blood from previous sacrifice.

The following day (ninth day, Navami), we would bring the other goat to the butcher’s shop. If you did not rise up early (just before dawn), you would be so far behind the line that you would have to wait hours until your turn came. For that day the street would be the butcher’s shop, for he would build a makeshift stove on a street corner and place a big open-top pot of boiling water. The slaughter went something like this: the butcher asks his assistant to hold the goat’s horns with each hand, the owner of the goat holds the hind legs with both hands as some owners were too afraid to hold the horns lest the butcher misses his target, the butcher places a block of wood on the ground right below the goat’s neck. Once the goat is positioned, the butcher sprinkles some water on the goats head, if the goat shakes its head it is now auspicious to kill the goat, if it doesn’t, the butcher waits for a while and tries again. Once the goat is ready, the butcher positions himself perpendicular to the goat, brings his crescent-shaped khukuri (traditional Nepali knife made of iron) high above his head and then with one strong downward swing strikes the goat’s neck. The goat is now completely decapitated, the butcher rushes to hold the body and squeezes the blood into a pan. He then starts skinning, gutting, cleaning, cutting, etc. The goat would be ready as meat in less than an hour.

For some reasons, kids in my neighborhood were fascinated to see the killing, on occasions some people would walk around with their big khukuri volunteering to do the killing, sometimes the killer (if he was just a novice) will have to attempt more than once to finish a single job. This macabre affair was celebrated by young and adults alike, all in the name of religion and festival. I guess violence is an innate human character, the beast within us rises on such occasions, affirming our belief that we are the supreme animals, the conquerors. The goat becomes a mute victim, a silent witness to such barbaric acts. I am still puzzled why I and other kids my age (I was around ten years older at that time) were fascinated with such acts of cruelty inflicted upon the goat. Not that I had a violent attitude. The whole episode of goat sacrificing and butchering was somewhat reassuring to me that my fate would be different from that of the poor goat, though I can’t still figure out what was so reassuring about it. The goat was innocent looking, often pitifully tied next to the one that was being slaughtered, its sad eyes pleading for mercy. Silence blanketed the early morning atmosphere, broken only by the occasional crackling noise coming from the burning firewood, the occasional yelp of the goats, the whacking sound of the knife, and the chatter of the few people that were around to witness the cruetly. The silence seemed ungodly, the dawn prophetic.

Sunday, September 13, 2009

Let's Go Fly a Kite

The nice thing about the start of Dashain was that it also coincided with the kite season. Now-a-days flying a kite in Kathmandu is not as common as it used to be, this splendid sport used to be the favorite pasttime of kids and adults alike in the 70s. One could see hundreds of kites on Kathmandu’s sky gliding elegantly or fighting a fierce battle with one another and pulling all the tricks it could to bring someone else down. I suppose the sport fell victim to growing popularity of technology-driven entertainment and ATARI and other games of the late 80s and 90s. Kite flying, marbles (guccha), tash (cards), and other sports like tel kasa (game that involves giving a chase), aas paas (hide and seek) began to disappear slowly and if you ask young kids these days if they played any such games I bet with the exception of kite flying they would not have a clue how these games are played.

Anyway, flying a kite gave us tremendous joy, just like how the author of The Kite Runner describes in the book. We had to go to Ason Tole to buy the best kites, the kites came in a dazzle of colors. The kite flying apparatus consisted of the kite (made of paper) itself, the wooden reel with two spools on either side which you had to hold in your hands to manipulate the kite as it is airborne. Miles and miles of string were rolled onto the reel. The string was often fortified with homemade manja, a mixture of crushed glass and thick adhesive. The strength of the string depended on the quality of the mixture. I was not good at flying kite; I tried several times but never could master the art. Some of my friends were excellent kite flyers so I used to visit them in their house. We would go to the roof and spent hours flying the kite and engaging with others on kite fights. Depending on wind conditions and wind directions, we positioned our kites in a way that it would reach very high up in the sky. The kite would slowly rise up, sometimes dancing like a beautiful ballerina, and at other times furious as a dragon warrior. We always made sure that before we engaged in a fight we had ample time to enjoy the high flying and the theatrics in the sky.

There were different types of kites in the sky, some were big some small. Some had “two color” pattern, some were three or four colors, most kites we flew were square shaped. Most Nepali kites were of the Malay variety: a two sticker without a tail, both sticks of equal length crossed and tied with center of one at a spot one-seventh the distance from the top of the other; a bridle attached to the kite had two legs, one from the top of the diamond and the other from the lowest point, meeting a little below the crossing of the sticks; a string pulled tight across the back of the cross stick bowed the surface making the kite self-balancing. The Nepali kites were mostly made of lokta hand-made paper. Because the kites did not come with a tail attached, sometimes, we would make the tails ourselves. It was a pure joy to see the kite twisting and turning its tail as it became airborne and flew higher and higher. The sight of the colorful kites against the blue sky and the sounds (of yells, hoots, cheers, laughs, and occasional curses) made kite flying a memorable affair.

The kite fights were intense, the successful fighters were those who could anticipate the moves of their rivals, and of course who had championed the art and whose strings were the strongest. The manja fortified strings could strike a terror on unsuspecting kites. On any given day, you could see several kite duels in the sky and even if you were just a spectator on the roof or on the street below you would cast an intense gaze toward the sky, your eyes sparkled with the thrill, your jaws shut tight due to the intensity, and your heart pounding at the prospect of catching the losing kite. You would stay focused on one of the many duels and would anticipate the right timing of one of the kites being cut loose and then run towards the falling kite to catch it. There were times when I was rewarded but there were also times when the kite just tore apart due to the intense shuffle amongst the kite runners. As a rule, if you were the first one to catch it other runners would let you have the kite, but it was well understood by kite runners that the moment you run toward the falling kite you were a gladiator racing against others who would come from different directions trying to be the first one to arrive. The race would almost always determine that there were no clear winners and a fist fight would ensue. It was one of the main reasons why I tried not to take part in the race; as if the fate of the falling kite was predetermined. On a few occasions, when my friends or I were lucky to be the winner of a bruised or battered kite, we would spent hours trying to resurrect it and let it fly one more time in the hopes that it might be able to challenge the victor. And when it did, the kite became our inspiration, a symbol of hope to restore lost glory, and a way to redeem ourselves. The next few days would be spent on telling the heroic tale to our friends in the neighborhood.

Anyway, flying a kite gave us tremendous joy, just like how the author of The Kite Runner describes in the book. We had to go to Ason Tole to buy the best kites, the kites came in a dazzle of colors. The kite flying apparatus consisted of the kite (made of paper) itself, the wooden reel with two spools on either side which you had to hold in your hands to manipulate the kite as it is airborne. Miles and miles of string were rolled onto the reel. The string was often fortified with homemade manja, a mixture of crushed glass and thick adhesive. The strength of the string depended on the quality of the mixture. I was not good at flying kite; I tried several times but never could master the art. Some of my friends were excellent kite flyers so I used to visit them in their house. We would go to the roof and spent hours flying the kite and engaging with others on kite fights. Depending on wind conditions and wind directions, we positioned our kites in a way that it would reach very high up in the sky. The kite would slowly rise up, sometimes dancing like a beautiful ballerina, and at other times furious as a dragon warrior. We always made sure that before we engaged in a fight we had ample time to enjoy the high flying and the theatrics in the sky.

There were different types of kites in the sky, some were big some small. Some had “two color” pattern, some were three or four colors, most kites we flew were square shaped. Most Nepali kites were of the Malay variety: a two sticker without a tail, both sticks of equal length crossed and tied with center of one at a spot one-seventh the distance from the top of the other; a bridle attached to the kite had two legs, one from the top of the diamond and the other from the lowest point, meeting a little below the crossing of the sticks; a string pulled tight across the back of the cross stick bowed the surface making the kite self-balancing. The Nepali kites were mostly made of lokta hand-made paper. Because the kites did not come with a tail attached, sometimes, we would make the tails ourselves. It was a pure joy to see the kite twisting and turning its tail as it became airborne and flew higher and higher. The sight of the colorful kites against the blue sky and the sounds (of yells, hoots, cheers, laughs, and occasional curses) made kite flying a memorable affair.

The kite fights were intense, the successful fighters were those who could anticipate the moves of their rivals, and of course who had championed the art and whose strings were the strongest. The manja fortified strings could strike a terror on unsuspecting kites. On any given day, you could see several kite duels in the sky and even if you were just a spectator on the roof or on the street below you would cast an intense gaze toward the sky, your eyes sparkled with the thrill, your jaws shut tight due to the intensity, and your heart pounding at the prospect of catching the losing kite. You would stay focused on one of the many duels and would anticipate the right timing of one of the kites being cut loose and then run towards the falling kite to catch it. There were times when I was rewarded but there were also times when the kite just tore apart due to the intense shuffle amongst the kite runners. As a rule, if you were the first one to catch it other runners would let you have the kite, but it was well understood by kite runners that the moment you run toward the falling kite you were a gladiator racing against others who would come from different directions trying to be the first one to arrive. The race would almost always determine that there were no clear winners and a fist fight would ensue. It was one of the main reasons why I tried not to take part in the race; as if the fate of the falling kite was predetermined. On a few occasions, when my friends or I were lucky to be the winner of a bruised or battered kite, we would spent hours trying to resurrect it and let it fly one more time in the hopes that it might be able to challenge the victor. And when it did, the kite became our inspiration, a symbol of hope to restore lost glory, and a way to redeem ourselves. The next few days would be spent on telling the heroic tale to our friends in the neighborhood.

Saturday, September 12, 2009

City of Gods

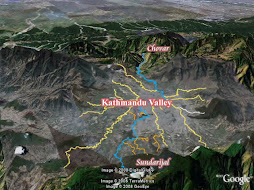

Today, I want to talk about something else, Dashain, the biggest festival celebrated by all Nepalese looms around the corner. As I have noted in my previous posting on rivers, I want to focus on what else made it worthwhile going to the rivers. I have mentioned the temple Pashupatinath on the Bagmati riverbank. But temples are found almost everywhere in Kathmandu, no wonder why it is also known as the city of gods (or temples). If you look carefully, at every nook and corner on the streets you will find a temple or a shrine. You could also tell if the neighborhood you are visiting (if you are a first time visitor to Kathmandu) is old or new. You see, the city core is literally dotted with thousands of temples, the old temples are built in a pagoda style, decorated with intricately carved doors, windows, and supporting structures. We don’t know how old are these temples but those at the city core may as well have been built hundreds of years ago. The gods and goddesses who were worshipped in these temples include the famous elephant god Ganesh, Vishnu, Mahadev, Durga, Bhairav, and dozens of others. Apart from Pashupatinath, other well-known temples in Kathmandu include Shobha Bhagavati, Taleju, Kathmandu Ganeshthan (than refers to a place or a location), Guheswori, the rain god Indra at Indrachowk (chowk refers to a courtyard or an intersection). Of these, the one that I frequented the most was Shobha Bhagavati on the banks of Bishnumati river. Not that I was a religious person, my grandfather was an orthodox Brahmin, he was educated and modern in his outlook, but when it came to traditional rituals and worships he was very conservative. Now, my foreign friends from the west will certainly be miffed that the Hindus regarded people from the west as untouchables (or of the fifth caste) due to their meat eating, alcohol drinking and other “unsanitary” habits. The orthodox Brahmins in Nepal called these people Mlechha. It was no wonder that Jung Bahadur (Bahadur means the brave one),the first Rana prime minister of Nepal, brought water with him from Nepal when he visited England upon Queen Victoria’s invitation.

On most occasions, I visited Shobha Bhagavati not for religious reasons but mostly to swim in the river. But during the festival of Dashain (it falls usually in early October and is celebrated for two weeks) my friends and I visited the temple every day from the first day of Ghatasthapana (which I briefly mentioned in my earlier posting) till the ninth day of Nava Ratri (in Sanskrit ninth night). Those were very memorable days. The temples would be very crowded early morning and we had to line up for hours to get inside the temple. So my friends would wake me up as early as 2:00 am in the morning by calling out my name very loud from the courtyard of our house. I would wake up (or sometimes it was my grandmother who would wake me up), clean myself, dress neatly and join the friends who would be waiting for me. We would then call a few more friends who had agreed to join us the day before, and then slowly head towards the temple. The earliest we could visit the better it was, for the line would be very short during that time. We would get inside the temple, do a quick prayer and then get out as fast as we could as the real fun was not to worship but to do people watching, especially watching girls of our own age, who would line up and wait for their turn to get in. We would just hang around casting glances here and there, looking for some familiar faces or just looking for a pretty face. This would go on for an hour or two, as we would visit other nearby temples, and my friends would tell stories of some macho adventures (like stealing fruits from neighborhood orchards or watching the latest Bollywood flick, or how certain girl seemed to have shown interest) or entertained us with their braggadocio. But the most rewarding of all this waking up early morning and gallivanting around was the stop at a teashop. During the festival seasons, teashops would open as early as four in the morning; drinking a hot cup of tea was always so much enjoyable during the cool autumn mornings that we would drink several cups depending on how much money we could collect between us. By the time I returned home I would have already spent six or seven hours with my friends. My grandfather never said anything about my coming home late as this was a festival season and I was doing my "religious duty". I wished everyday was like those ten days of Dashain where I roamed freely and without care.

The atmosphere on the streets was worth the trouble getting up so early in the morning. You would see a folk band playing their traditional instruments marching toward or returning from the temples. Flutes, clarinets, drums and cymbals were the typical instruments played by the bands. Members of the brand had brightly colored red and yellow tika on their forehead, and marigold flowers on their heads or around their necks. As if the gods were hiding in the clouds and were cheering for these band, the whole atmosphere was joyous and spiritual; there was something sacred about it. The cool morning son glowed on cheerful faces; people seemed so content and happy as if they had forgotten all their troubles and left their cares behind. Growing up, I always cherished those solemn occasions and blissful moments, which remind me that life can be simple yet beautiful.

The festival of Dashain (also called Vijaya Dashami) is celebrated for ten days, the tenth day being the grand culmination of nine days of worshiping. It is the biggest festival of Nepal, when even the government shuts down for several days. In some ways, it is like Christmas when friends and relatives from far and wide meet and greet each other, families reunite, and past grievances are forgotten. My grandfather changed the furnishings at home and all of us received new clothes, shoes, sweets and money. On the tenth day, our family priest visited the house and after the rituals of worshipping and cleansing the house put red tika on our foreheads and the jamara (barley plants) which by now would be bright yellow and some six inches long. We would all gather in my grandfather’s room, all dressed in new clothes; the men and boys looked handsome and cheerful, women and girls looked elegant and beautiful in their clothes and gold jewelries. All of us would receive tika and jamara one by one from my grandfather; the tradition was to start with the elders down to the youngest member of the family. After the tika, we would all eat together; lunch was typically goat meat (the goat sacrificed either on the eighth (Asthami) or the ninth day (Navami) of Dashain), rice, the best vegetables that one could buy in the market that day, and pickled radish and cucumber. I was really happy to see all my family (my parents came home to Kathmandu) and felt great satisfaction to be surrounded by loved ones. I wished the day lingered for a little while longer.

On most occasions, I visited Shobha Bhagavati not for religious reasons but mostly to swim in the river. But during the festival of Dashain (it falls usually in early October and is celebrated for two weeks) my friends and I visited the temple every day from the first day of Ghatasthapana (which I briefly mentioned in my earlier posting) till the ninth day of Nava Ratri (in Sanskrit ninth night). Those were very memorable days. The temples would be very crowded early morning and we had to line up for hours to get inside the temple. So my friends would wake me up as early as 2:00 am in the morning by calling out my name very loud from the courtyard of our house. I would wake up (or sometimes it was my grandmother who would wake me up), clean myself, dress neatly and join the friends who would be waiting for me. We would then call a few more friends who had agreed to join us the day before, and then slowly head towards the temple. The earliest we could visit the better it was, for the line would be very short during that time. We would get inside the temple, do a quick prayer and then get out as fast as we could as the real fun was not to worship but to do people watching, especially watching girls of our own age, who would line up and wait for their turn to get in. We would just hang around casting glances here and there, looking for some familiar faces or just looking for a pretty face. This would go on for an hour or two, as we would visit other nearby temples, and my friends would tell stories of some macho adventures (like stealing fruits from neighborhood orchards or watching the latest Bollywood flick, or how certain girl seemed to have shown interest) or entertained us with their braggadocio. But the most rewarding of all this waking up early morning and gallivanting around was the stop at a teashop. During the festival seasons, teashops would open as early as four in the morning; drinking a hot cup of tea was always so much enjoyable during the cool autumn mornings that we would drink several cups depending on how much money we could collect between us. By the time I returned home I would have already spent six or seven hours with my friends. My grandfather never said anything about my coming home late as this was a festival season and I was doing my "religious duty". I wished everyday was like those ten days of Dashain where I roamed freely and without care.

The atmosphere on the streets was worth the trouble getting up so early in the morning. You would see a folk band playing their traditional instruments marching toward or returning from the temples. Flutes, clarinets, drums and cymbals were the typical instruments played by the bands. Members of the brand had brightly colored red and yellow tika on their forehead, and marigold flowers on their heads or around their necks. As if the gods were hiding in the clouds and were cheering for these band, the whole atmosphere was joyous and spiritual; there was something sacred about it. The cool morning son glowed on cheerful faces; people seemed so content and happy as if they had forgotten all their troubles and left their cares behind. Growing up, I always cherished those solemn occasions and blissful moments, which remind me that life can be simple yet beautiful.

The festival of Dashain (also called Vijaya Dashami) is celebrated for ten days, the tenth day being the grand culmination of nine days of worshiping. It is the biggest festival of Nepal, when even the government shuts down for several days. In some ways, it is like Christmas when friends and relatives from far and wide meet and greet each other, families reunite, and past grievances are forgotten. My grandfather changed the furnishings at home and all of us received new clothes, shoes, sweets and money. On the tenth day, our family priest visited the house and after the rituals of worshipping and cleansing the house put red tika on our foreheads and the jamara (barley plants) which by now would be bright yellow and some six inches long. We would all gather in my grandfather’s room, all dressed in new clothes; the men and boys looked handsome and cheerful, women and girls looked elegant and beautiful in their clothes and gold jewelries. All of us would receive tika and jamara one by one from my grandfather; the tradition was to start with the elders down to the youngest member of the family. After the tika, we would all eat together; lunch was typically goat meat (the goat sacrificed either on the eighth (Asthami) or the ninth day (Navami) of Dashain), rice, the best vegetables that one could buy in the market that day, and pickled radish and cucumber. I was really happy to see all my family (my parents came home to Kathmandu) and felt great satisfaction to be surrounded by loved ones. I wished the day lingered for a little while longer.

Sunday, August 30, 2009

Field of Dreams

One day in Nawalpur several staff from my dad’s office decided that they needed to visit Narayan Ghat for some official business. The office had a Russian-made jeep (as I have said before everything that looked like the American “Jeep” was jeep to us). So I tagged along with my parents. I remember a few things about that trip. We all were cramped in the jeep, there could have been more than ten people on it. The jeep had trouble making over a steep hill near Daune Danda (this was the highest point between Narayan Ghat and Nawalpur), some of us had to get off so the driver could safely reach the hill top where he waited for us. From the hill looking down, we saw several black things along the Narayani riverbanks. We were told they were the crocodiles basking in the sun. At Narayan Ghat while the husbands attended to office duty, their families decided to go to the cinema. Indeed, cinema was a real treat for many of us including myself.

My grandfather used to take me with him every time he wanted to see a movie. He was a movie buff, and saw the same movie several times; back then going to the cinema was a major event, and was well-planned in advance. There were five theaters in Kathmandu Valley – Jay Nepal Chitraghar, Ranjana Cinema Hall and Biswo Jyoti in Kathmandu; Ashok Cinema in Patan; and Nava Durga Chitra Mandir in Bhaktapur. The ones in Kathmandu were 20 odd minutes from our house. Anyway, my grandfather made sure that I gave him company; as long as the kids were with their parents or an adult they could see movies for free. Most movies shown in the cinemas were from Bollywood. A typical Bollywood movie would be three hours long, the main story punctuated by several song and dance numbers. Bollywood songs were very popular in Kathmandu where they were repeatedly played out on Nepal Radio. My mother is from the south (Janakpur, a border town) so going to the cinema for her was a natural thing to do. Besides, movie was the only modern form of entertainment for many Nepalese as there was no television at that time. I was deeply influenced by Bollywood movies and songs. As it turns out, I had a talent for singing. I did not know back then, but it appears the talent for singing was passed from my mother'side of families. In my case, it was my mother. I will have some more postings on Bollywood movies and Hindi songs, as these were critical to my upbringing, and provide an interesting narrative to my memories.

So on a hot afternoon we all landed in Narayan Ghat’s cinema hall where “Balram Shree Krishna (1968 release) was playing. The story is about the Hindu god Krishna and his elder brother Balram, both make a formidable pair and fight the bad guys in the movie. Honestly, I don’t remember anything about the movie. What I remember is several moviegoers walked out frequently as the heat inside the cinema hall was almost unbearable. The sweat from neatly packed bodies in the theater, combined with the smoke from cigarettes made it impossible to watch the movie in one go. It turns out that the cinema hall was a newly converted warehouse, the ventilation was awful, and the fans far in between. But who would miss the chance to see such an exciting movie? During the movie,I went out only once and that was not because I wanted to get away from the heat but because I had to use the bathroom.

On another such occasion, my father and I visited our homestead in Chitwan, eight kilometers east from Narayan Ghat. My uncle had been living in Chitwan for some time and was taking care of the land. Our house was in the middle of the farm, it was a crudely built timber cottage with thatch grasses as roof. On the north side of the house there was a chicken pen and a goat corral. Our visit occurred during the rice harvesting season. I saw many people on our farm. I suppose they were either hired hands or neighbors who had come to help my uncle in exchange for his help at a later time. Some of them were using sickles to cut paddy, others were carrying the paddies which were neatly bundled and transported to a place near the house. It was my first time to witness a rice harvest. Villagers asked my father about me as this was the first time they had ever seen me. I tagged behind my dad, shying away from all the inquisitive eyes, and refraining myself from talking to them. Our farm land was adjacent to a dense forest (Barandabar); there were several tall Sal trees still standing on our land, remnants of what used to be a dense forest. Remember, both Nawalpur and Chitwan (combinedly Rapti Valley) were new settlements, where migrants from the central hills had moved in to seek their fortunes in the new promised land. Alas, no one had told them how difficult their life would be, what wild things they would encounter, and how some of them eventually would have to return to their original homes. Meanwhile, I was enjoying my very short visit to Chitwan; people seemed friendly and hardworking. There was no electricity, water came from the wells hand dug into the ground. Interestingly, the water table was very high; one could find water after digging a hole of about ten feet. People were singing (it is customary to sing while doing farm work) and chatting, as if the work was not hard but fun. I looked further away and saw blue mountains, far behind were the snow capped mighty Himalaya. The paddy fields were alternated by brightly colored mustard fields. There were green and yellow fields on the foreground, blue and white mountains in the background, clear blue sky overhead, and emerald green forest behind me. It felt like I was in a Bollywood dream sequence.

My grandfather used to take me with him every time he wanted to see a movie. He was a movie buff, and saw the same movie several times; back then going to the cinema was a major event, and was well-planned in advance. There were five theaters in Kathmandu Valley – Jay Nepal Chitraghar, Ranjana Cinema Hall and Biswo Jyoti in Kathmandu; Ashok Cinema in Patan; and Nava Durga Chitra Mandir in Bhaktapur. The ones in Kathmandu were 20 odd minutes from our house. Anyway, my grandfather made sure that I gave him company; as long as the kids were with their parents or an adult they could see movies for free. Most movies shown in the cinemas were from Bollywood. A typical Bollywood movie would be three hours long, the main story punctuated by several song and dance numbers. Bollywood songs were very popular in Kathmandu where they were repeatedly played out on Nepal Radio. My mother is from the south (Janakpur, a border town) so going to the cinema for her was a natural thing to do. Besides, movie was the only modern form of entertainment for many Nepalese as there was no television at that time. I was deeply influenced by Bollywood movies and songs. As it turns out, I had a talent for singing. I did not know back then, but it appears the talent for singing was passed from my mother'side of families. In my case, it was my mother. I will have some more postings on Bollywood movies and Hindi songs, as these were critical to my upbringing, and provide an interesting narrative to my memories.

So on a hot afternoon we all landed in Narayan Ghat’s cinema hall where “Balram Shree Krishna (1968 release) was playing. The story is about the Hindu god Krishna and his elder brother Balram, both make a formidable pair and fight the bad guys in the movie. Honestly, I don’t remember anything about the movie. What I remember is several moviegoers walked out frequently as the heat inside the cinema hall was almost unbearable. The sweat from neatly packed bodies in the theater, combined with the smoke from cigarettes made it impossible to watch the movie in one go. It turns out that the cinema hall was a newly converted warehouse, the ventilation was awful, and the fans far in between. But who would miss the chance to see such an exciting movie? During the movie,I went out only once and that was not because I wanted to get away from the heat but because I had to use the bathroom.

On another such occasion, my father and I visited our homestead in Chitwan, eight kilometers east from Narayan Ghat. My uncle had been living in Chitwan for some time and was taking care of the land. Our house was in the middle of the farm, it was a crudely built timber cottage with thatch grasses as roof. On the north side of the house there was a chicken pen and a goat corral. Our visit occurred during the rice harvesting season. I saw many people on our farm. I suppose they were either hired hands or neighbors who had come to help my uncle in exchange for his help at a later time. Some of them were using sickles to cut paddy, others were carrying the paddies which were neatly bundled and transported to a place near the house. It was my first time to witness a rice harvest. Villagers asked my father about me as this was the first time they had ever seen me. I tagged behind my dad, shying away from all the inquisitive eyes, and refraining myself from talking to them. Our farm land was adjacent to a dense forest (Barandabar); there were several tall Sal trees still standing on our land, remnants of what used to be a dense forest. Remember, both Nawalpur and Chitwan (combinedly Rapti Valley) were new settlements, where migrants from the central hills had moved in to seek their fortunes in the new promised land. Alas, no one had told them how difficult their life would be, what wild things they would encounter, and how some of them eventually would have to return to their original homes. Meanwhile, I was enjoying my very short visit to Chitwan; people seemed friendly and hardworking. There was no electricity, water came from the wells hand dug into the ground. Interestingly, the water table was very high; one could find water after digging a hole of about ten feet. People were singing (it is customary to sing while doing farm work) and chatting, as if the work was not hard but fun. I looked further away and saw blue mountains, far behind were the snow capped mighty Himalaya. The paddy fields were alternated by brightly colored mustard fields. There were green and yellow fields on the foreground, blue and white mountains in the background, clear blue sky overhead, and emerald green forest behind me. It felt like I was in a Bollywood dream sequence.

A “Country” Paradise

While the trip to Nawalpur visiting my parents, as described in my previous posting, was quite thrilling, my stay there was almost uneventful. I liked the village. The Resettlement Office was a small building and nearby was my father’s government quarters. I recall it was mostly a small thatched roof cottage, but was spacious enough for us (my parents and my two sisters). The government office and a public elementary school were the only concrete buildings in the village. Even though I was expected to be there for two months, my parents decided that I should go to school, it was on odd time going to school, that is, I was enrolling two months before the final exams. I guess the school headmaster was impressed by the fact that I was from Kathmandu. Anyway, I started going to school everyday shortly before 10 am and until four pm.

From what I recall, the government office was almost at the center of the village, a little to the southwest was our cottage, the school was less than five minutes walk east from our cottage, and there were a few huts and cottages north of the office lined up on the main street. A few minutes down the street (east direction) was the graveled highway to Narayanghat. The village was nothing more than a hamlet established in the middle of the dense jungle growth. Aside from going to school, there was not much else to do. I started hanging out with some local boys (I don’t know if they were transplanted just like me) and explored nearby places. The school was perched upon a hill. It was not really a hill, the dirt track from the highway dipped a little bit rising as it reached the village center. Just before the rise, one had to cross a small stream, toward the left a track led up to the school. I remember spending hours with some friends wading in the shallow pools of water and trying to catch fish with our tiny hands. The water was knee deep and clear, you could see the pebbles on the bottom and the fish running in unison in different directions. It gave me immense pleasure to see the small fish trying to escape from our hands, the cool touch of water (even though it was a Fall season, afternoon temperatures could be very high in the Terai), and the jungle surroundings. My days were carefree, pampered, and I always found something to do. Sometimes we visited the government-owned barn where we could pay a visit to a large brown horse. This was also the first time I rode a horse, I didn't last very long on horseback.

All in all, life in the country was completely different from Kathmandu. It was peaceful, harmonious and without events, except for one night when it seemed the whole village was going in flames. The Fall season in Terai is usually very dry except for the morning dews. So one night, as we were finishing our dinner we saw flames rising above us. One of the houses north from ours was up in flames, I recall vividly how high the flames were rising. The flames were twisting and twirling like Shiva’s furious dance moves, everyone was out, some were trying to help put out the fire, others were standing shell-shocked. In a matter of minutes the house was burnt to the ground. Next morning I went out with my parents to check the aftermath of the fire and to express our sympathies to the family. The place was covered with black soot and hardly anything was left worth salvaging. I felt very bad for the family, one of their girls was in the same class that I was in (Grade Four). The Year was 1969.

From what I recall, the government office was almost at the center of the village, a little to the southwest was our cottage, the school was less than five minutes walk east from our cottage, and there were a few huts and cottages north of the office lined up on the main street. A few minutes down the street (east direction) was the graveled highway to Narayanghat. The village was nothing more than a hamlet established in the middle of the dense jungle growth. Aside from going to school, there was not much else to do. I started hanging out with some local boys (I don’t know if they were transplanted just like me) and explored nearby places. The school was perched upon a hill. It was not really a hill, the dirt track from the highway dipped a little bit rising as it reached the village center. Just before the rise, one had to cross a small stream, toward the left a track led up to the school. I remember spending hours with some friends wading in the shallow pools of water and trying to catch fish with our tiny hands. The water was knee deep and clear, you could see the pebbles on the bottom and the fish running in unison in different directions. It gave me immense pleasure to see the small fish trying to escape from our hands, the cool touch of water (even though it was a Fall season, afternoon temperatures could be very high in the Terai), and the jungle surroundings. My days were carefree, pampered, and I always found something to do. Sometimes we visited the government-owned barn where we could pay a visit to a large brown horse. This was also the first time I rode a horse, I didn't last very long on horseback.

All in all, life in the country was completely different from Kathmandu. It was peaceful, harmonious and without events, except for one night when it seemed the whole village was going in flames. The Fall season in Terai is usually very dry except for the morning dews. So one night, as we were finishing our dinner we saw flames rising above us. One of the houses north from ours was up in flames, I recall vividly how high the flames were rising. The flames were twisting and twirling like Shiva’s furious dance moves, everyone was out, some were trying to help put out the fire, others were standing shell-shocked. In a matter of minutes the house was burnt to the ground. Next morning I went out with my parents to check the aftermath of the fire and to express our sympathies to the family. The place was covered with black soot and hardly anything was left worth salvaging. I felt very bad for the family, one of their girls was in the same class that I was in (Grade Four). The Year was 1969.

Monday, August 10, 2009

Trouble in Paradise

I guess, it was “written” that I would become a professor of tourism, specializing on management of natural resources and tourism impacts in remote areas. I find it rather interesting how early encounters with wildlife shape future careers. The curiosity about places other than my own hometown planted in me a seed for my future adventures, some of which were utterly reckless. Encounters with wildlife also started with a bizarre set of events. As I wrote in a previous posting, I am really afraid of snakes. I am curious about snakes, thrilled to see it crawling (this makes hair on my spine stand up!), but will not go closer even if it is dead. My mom tells me that when I was a two-month old baby, she had taken me to Khajuri where all kinds of venomous snakes crawled around. King Cobras were common; I am fortunate not to have seen it in the wild. I have seen big Dhamans (Ptyas mucosus) on the banks of Devata Pokhari. So my mom puts me on bed for an afternoon nap. My grandparent’s house in Khajuri consisted of two modest buildings. The walls were made of a reed-mud combination and the roof had cylindrical-shaped tiles. The two buildings were separated by a courtyard in the middle and gardens on the sides. It was a custom in the village to spend the afternoon mostly in the verandah or the courtyard because it would get terribly hot during summer. Anyway, I was sleeping on a make-shift bed on the ground. All of a sudden, there was a big snake underneath my bed. Everybody was panicking and did not know what to do, no one dared to come close to me. So there I was surrounded by a big snake, and I could do nothing about it (my mom told me that I was sound asleep). Fortunately, the snake slithered away after sometime and everybody rejoiced that nothing bad happened to me. May be snake phobia is in my genes, as I know that my mom and I react exactly the same way whenever we see a snake.