Another interesting aspect of Dashain was the various animal sacrifices offered to goddess Bhavani. The Brahmin hindus mostly preferred to sacrifice a goat, whereas the Newar hindus sacrificed either chicken/duck or buffalo. The ritual of sacrifice was elaborate and often planned days or even weeks in advance. Individual families would spend several days searching for the perfect animal in the livestock market. In our case, the search party involved mostly my grandfather, accompanied by his grandchildren (myself and my cousins), and occasionally by my uncle too. So we would visit the livestock market in Tundikhel (this was the 70s) looking for a young, healthy goat that had no obvious marks (bruises, cuts etc.) on its body and had thick and shiny black fur. Only when black goats were not available we would select a brown or a white goat. I don’t think we ever had to select a goat that was not black. This sometimes meant paying a premium price for the goat, as every family wanted the sacrificial goat to be as perfect as it could be.

While visiting the livestock market was fun, the whole affair of goat selection and the subsequent sacrifice was horrible for the poor animal. Once the selection was determined, my grandfather and my uncle negotiated the price with the seller and this sometimes required a mastery of the art of negotiation. You pretended that you are walking away from the sale looking for another seller, sometimes you argued why the goat was not worth its price by drawing the owner’s attention to the physical defects of the animal. Not that the animal really had a defect, it’s just that you needed something to be critical about in the hopes that the seller would soften a little bit. During Dashain time it was often customary to buy a pair of goats, the young one (Boka in Nepali, male, not neutered) would be sacrificed at the temple, the matured one (Khasi, male, neutered) would be slaughtered at the neighborhood butcher’s shop. The goats were tied with a short rope around their neck, we would hold the rope and let them follow us. If the goat was too stubborn to leave its other companions at the market, one of us got behind it and hit its hind legs with a small stick or with our palm. The journey home would often be very interesting. If taxis were available, we would take the taxi and put the goat in the trunk. But if we had to walk home, this would entail a very careful navigation of the streets through Asan and Chettrapati, which were crowded with people shopping for Dashain. Sometimes the goat would set itself free from our hands and dart across the street, we had to run after it as fast as it could, as losing it meant not only a couple hundred rupees gone down the drain but also initiating the search all over again. Once home, we played with the goats feeding them grass or corn, and teasing and torturing by all means possible. Because we didn’t really have a place for the goat in our house, typically we bought the goats a day or two ahead of the sacrifice. I often wondered what the goats felt when they were separated from their family or companions, and when they had to walk through the busy street and tolerate the humiliation we inflicted upon them. One thing was sure, I did not want to be one of those poor goats, which was raised, and ironically, even loved just to be sacrificed to fulfill our religious practices and beliefs. Never did I question why the goats had to live and die that way, we were simply doing what everybody did in the name of celebrating Dashain.

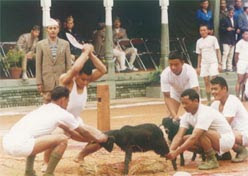

On the fateful day (the eighth day or Ashtami), my uncle and I would bring the black goat to Shoba Bhagavati temple. The temple organizers always separated worshippers in three lines: male worshippers, female worshipper, and those with sacrificial animals. I have witnessed these sacrifices without any feelings of guilt, emotion or stress. I think I was inhumanely indifferent to the animal. The priest’s aide would grab the goat by its neck with his left hand, the knife on his right hand, his knee holding the lower part of the goat's body lest it sets itself free. He would then pierce the lower neck with the knife and run it across the neck, the blood that squeezed was offered to the goddess. After a while the goat would be silent, decapitated and ready to be put in a jute sack and carried home for butchering and then feasting. All this would occur in the early hours of the day, usually before six in the morning. The sacrifice, it was believed, would bring us happiness, peace and prosperity. At that time I had no doubts it brought us happiness – we would be feasting on delicious goat meat later during the day. About peace, I don’t know, I certainly thought that even the goat knew its fate as soon as it was brought before the goddess, and perhaps it felt an inner peace while accepting its impending fate. The strange thing was the goat never made any fuss (it did not yelp or made any noise) about being sacrificed even when it saw the priest’s aide and his sharp knife still dripping with fresh blood from previous sacrifice.

The following day (ninth day, Navami), we would bring the other goat to the butcher’s shop. If you did not rise up early (just before dawn), you would be so far behind the line that you would have to wait hours until your turn came. For that day the street would be the butcher’s shop, for he would build a makeshift stove on a street corner and place a big open-top pot of boiling water. The slaughter went something like this: the butcher asks his assistant to hold the goat’s horns with each hand, the owner of the goat holds the hind legs with both hands as some owners were too afraid to hold the horns lest the butcher misses his target, the butcher places a block of wood on the ground right below the goat’s neck. Once the goat is positioned, the butcher sprinkles some water on the goats head, if the goat shakes its head it is now auspicious to kill the goat, if it doesn’t, the butcher waits for a while and tries again. Once the goat is ready, the butcher positions himself perpendicular to the goat, brings his crescent-shaped khukuri (traditional Nepali knife made of iron) high above his head and then with one strong downward swing strikes the goat’s neck. The goat is now completely decapitated, the butcher rushes to hold the body and squeezes the blood into a pan. He then starts skinning, gutting, cleaning, cutting, etc. The goat would be ready as meat in less than an hour.

For some reasons, kids in my neighborhood were fascinated to see the killing, on occasions some people would walk around with their big khukuri volunteering to do the killing, sometimes the killer (if he was just a novice) will have to attempt more than once to finish a single job. This macabre affair was celebrated by young and adults alike, all in the name of religion and festival. I guess violence is an innate human character, the beast within us rises on such occasions, affirming our belief that we are the supreme animals, the conquerors. The goat becomes a mute victim, a silent witness to such barbaric acts. I am still puzzled why I and other kids my age (I was around ten years older at that time) were fascinated with such acts of cruelty inflicted upon the goat. Not that I had a violent attitude. The whole episode of goat sacrificing and butchering was somewhat reassuring to me that my fate would be different from that of the poor goat, though I can’t still figure out what was so reassuring about it. The goat was innocent looking, often pitifully tied next to the one that was being slaughtered, its sad eyes pleading for mercy. Silence blanketed the early morning atmosphere, broken only by the occasional crackling noise coming from the burning firewood, the occasional yelp of the goats, the whacking sound of the knife, and the chatter of the few people that were around to witness the cruetly. The silence seemed ungodly, the dawn prophetic.

Saturday, September 26, 2009

Sunday, September 13, 2009

Let's Go Fly a Kite

The nice thing about the start of Dashain was that it also coincided with the kite season. Now-a-days flying a kite in Kathmandu is not as common as it used to be, this splendid sport used to be the favorite pasttime of kids and adults alike in the 70s. One could see hundreds of kites on Kathmandu’s sky gliding elegantly or fighting a fierce battle with one another and pulling all the tricks it could to bring someone else down. I suppose the sport fell victim to growing popularity of technology-driven entertainment and ATARI and other games of the late 80s and 90s. Kite flying, marbles (guccha), tash (cards), and other sports like tel kasa (game that involves giving a chase), aas paas (hide and seek) began to disappear slowly and if you ask young kids these days if they played any such games I bet with the exception of kite flying they would not have a clue how these games are played.

Anyway, flying a kite gave us tremendous joy, just like how the author of The Kite Runner describes in the book. We had to go to Ason Tole to buy the best kites, the kites came in a dazzle of colors. The kite flying apparatus consisted of the kite (made of paper) itself, the wooden reel with two spools on either side which you had to hold in your hands to manipulate the kite as it is airborne. Miles and miles of string were rolled onto the reel. The string was often fortified with homemade manja, a mixture of crushed glass and thick adhesive. The strength of the string depended on the quality of the mixture. I was not good at flying kite; I tried several times but never could master the art. Some of my friends were excellent kite flyers so I used to visit them in their house. We would go to the roof and spent hours flying the kite and engaging with others on kite fights. Depending on wind conditions and wind directions, we positioned our kites in a way that it would reach very high up in the sky. The kite would slowly rise up, sometimes dancing like a beautiful ballerina, and at other times furious as a dragon warrior. We always made sure that before we engaged in a fight we had ample time to enjoy the high flying and the theatrics in the sky.

There were different types of kites in the sky, some were big some small. Some had “two color” pattern, some were three or four colors, most kites we flew were square shaped. Most Nepali kites were of the Malay variety: a two sticker without a tail, both sticks of equal length crossed and tied with center of one at a spot one-seventh the distance from the top of the other; a bridle attached to the kite had two legs, one from the top of the diamond and the other from the lowest point, meeting a little below the crossing of the sticks; a string pulled tight across the back of the cross stick bowed the surface making the kite self-balancing. The Nepali kites were mostly made of lokta hand-made paper. Because the kites did not come with a tail attached, sometimes, we would make the tails ourselves. It was a pure joy to see the kite twisting and turning its tail as it became airborne and flew higher and higher. The sight of the colorful kites against the blue sky and the sounds (of yells, hoots, cheers, laughs, and occasional curses) made kite flying a memorable affair.

The kite fights were intense, the successful fighters were those who could anticipate the moves of their rivals, and of course who had championed the art and whose strings were the strongest. The manja fortified strings could strike a terror on unsuspecting kites. On any given day, you could see several kite duels in the sky and even if you were just a spectator on the roof or on the street below you would cast an intense gaze toward the sky, your eyes sparkled with the thrill, your jaws shut tight due to the intensity, and your heart pounding at the prospect of catching the losing kite. You would stay focused on one of the many duels and would anticipate the right timing of one of the kites being cut loose and then run towards the falling kite to catch it. There were times when I was rewarded but there were also times when the kite just tore apart due to the intense shuffle amongst the kite runners. As a rule, if you were the first one to catch it other runners would let you have the kite, but it was well understood by kite runners that the moment you run toward the falling kite you were a gladiator racing against others who would come from different directions trying to be the first one to arrive. The race would almost always determine that there were no clear winners and a fist fight would ensue. It was one of the main reasons why I tried not to take part in the race; as if the fate of the falling kite was predetermined. On a few occasions, when my friends or I were lucky to be the winner of a bruised or battered kite, we would spent hours trying to resurrect it and let it fly one more time in the hopes that it might be able to challenge the victor. And when it did, the kite became our inspiration, a symbol of hope to restore lost glory, and a way to redeem ourselves. The next few days would be spent on telling the heroic tale to our friends in the neighborhood.

Anyway, flying a kite gave us tremendous joy, just like how the author of The Kite Runner describes in the book. We had to go to Ason Tole to buy the best kites, the kites came in a dazzle of colors. The kite flying apparatus consisted of the kite (made of paper) itself, the wooden reel with two spools on either side which you had to hold in your hands to manipulate the kite as it is airborne. Miles and miles of string were rolled onto the reel. The string was often fortified with homemade manja, a mixture of crushed glass and thick adhesive. The strength of the string depended on the quality of the mixture. I was not good at flying kite; I tried several times but never could master the art. Some of my friends were excellent kite flyers so I used to visit them in their house. We would go to the roof and spent hours flying the kite and engaging with others on kite fights. Depending on wind conditions and wind directions, we positioned our kites in a way that it would reach very high up in the sky. The kite would slowly rise up, sometimes dancing like a beautiful ballerina, and at other times furious as a dragon warrior. We always made sure that before we engaged in a fight we had ample time to enjoy the high flying and the theatrics in the sky.

There were different types of kites in the sky, some were big some small. Some had “two color” pattern, some were three or four colors, most kites we flew were square shaped. Most Nepali kites were of the Malay variety: a two sticker without a tail, both sticks of equal length crossed and tied with center of one at a spot one-seventh the distance from the top of the other; a bridle attached to the kite had two legs, one from the top of the diamond and the other from the lowest point, meeting a little below the crossing of the sticks; a string pulled tight across the back of the cross stick bowed the surface making the kite self-balancing. The Nepali kites were mostly made of lokta hand-made paper. Because the kites did not come with a tail attached, sometimes, we would make the tails ourselves. It was a pure joy to see the kite twisting and turning its tail as it became airborne and flew higher and higher. The sight of the colorful kites against the blue sky and the sounds (of yells, hoots, cheers, laughs, and occasional curses) made kite flying a memorable affair.

The kite fights were intense, the successful fighters were those who could anticipate the moves of their rivals, and of course who had championed the art and whose strings were the strongest. The manja fortified strings could strike a terror on unsuspecting kites. On any given day, you could see several kite duels in the sky and even if you were just a spectator on the roof or on the street below you would cast an intense gaze toward the sky, your eyes sparkled with the thrill, your jaws shut tight due to the intensity, and your heart pounding at the prospect of catching the losing kite. You would stay focused on one of the many duels and would anticipate the right timing of one of the kites being cut loose and then run towards the falling kite to catch it. There were times when I was rewarded but there were also times when the kite just tore apart due to the intense shuffle amongst the kite runners. As a rule, if you were the first one to catch it other runners would let you have the kite, but it was well understood by kite runners that the moment you run toward the falling kite you were a gladiator racing against others who would come from different directions trying to be the first one to arrive. The race would almost always determine that there were no clear winners and a fist fight would ensue. It was one of the main reasons why I tried not to take part in the race; as if the fate of the falling kite was predetermined. On a few occasions, when my friends or I were lucky to be the winner of a bruised or battered kite, we would spent hours trying to resurrect it and let it fly one more time in the hopes that it might be able to challenge the victor. And when it did, the kite became our inspiration, a symbol of hope to restore lost glory, and a way to redeem ourselves. The next few days would be spent on telling the heroic tale to our friends in the neighborhood.

Saturday, September 12, 2009

City of Gods

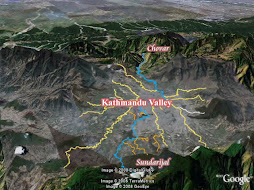

Today, I want to talk about something else, Dashain, the biggest festival celebrated by all Nepalese looms around the corner. As I have noted in my previous posting on rivers, I want to focus on what else made it worthwhile going to the rivers. I have mentioned the temple Pashupatinath on the Bagmati riverbank. But temples are found almost everywhere in Kathmandu, no wonder why it is also known as the city of gods (or temples). If you look carefully, at every nook and corner on the streets you will find a temple or a shrine. You could also tell if the neighborhood you are visiting (if you are a first time visitor to Kathmandu) is old or new. You see, the city core is literally dotted with thousands of temples, the old temples are built in a pagoda style, decorated with intricately carved doors, windows, and supporting structures. We don’t know how old are these temples but those at the city core may as well have been built hundreds of years ago. The gods and goddesses who were worshipped in these temples include the famous elephant god Ganesh, Vishnu, Mahadev, Durga, Bhairav, and dozens of others. Apart from Pashupatinath, other well-known temples in Kathmandu include Shobha Bhagavati, Taleju, Kathmandu Ganeshthan (than refers to a place or a location), Guheswori, the rain god Indra at Indrachowk (chowk refers to a courtyard or an intersection). Of these, the one that I frequented the most was Shobha Bhagavati on the banks of Bishnumati river. Not that I was a religious person, my grandfather was an orthodox Brahmin, he was educated and modern in his outlook, but when it came to traditional rituals and worships he was very conservative. Now, my foreign friends from the west will certainly be miffed that the Hindus regarded people from the west as untouchables (or of the fifth caste) due to their meat eating, alcohol drinking and other “unsanitary” habits. The orthodox Brahmins in Nepal called these people Mlechha. It was no wonder that Jung Bahadur (Bahadur means the brave one),the first Rana prime minister of Nepal, brought water with him from Nepal when he visited England upon Queen Victoria’s invitation.

On most occasions, I visited Shobha Bhagavati not for religious reasons but mostly to swim in the river. But during the festival of Dashain (it falls usually in early October and is celebrated for two weeks) my friends and I visited the temple every day from the first day of Ghatasthapana (which I briefly mentioned in my earlier posting) till the ninth day of Nava Ratri (in Sanskrit ninth night). Those were very memorable days. The temples would be very crowded early morning and we had to line up for hours to get inside the temple. So my friends would wake me up as early as 2:00 am in the morning by calling out my name very loud from the courtyard of our house. I would wake up (or sometimes it was my grandmother who would wake me up), clean myself, dress neatly and join the friends who would be waiting for me. We would then call a few more friends who had agreed to join us the day before, and then slowly head towards the temple. The earliest we could visit the better it was, for the line would be very short during that time. We would get inside the temple, do a quick prayer and then get out as fast as we could as the real fun was not to worship but to do people watching, especially watching girls of our own age, who would line up and wait for their turn to get in. We would just hang around casting glances here and there, looking for some familiar faces or just looking for a pretty face. This would go on for an hour or two, as we would visit other nearby temples, and my friends would tell stories of some macho adventures (like stealing fruits from neighborhood orchards or watching the latest Bollywood flick, or how certain girl seemed to have shown interest) or entertained us with their braggadocio. But the most rewarding of all this waking up early morning and gallivanting around was the stop at a teashop. During the festival seasons, teashops would open as early as four in the morning; drinking a hot cup of tea was always so much enjoyable during the cool autumn mornings that we would drink several cups depending on how much money we could collect between us. By the time I returned home I would have already spent six or seven hours with my friends. My grandfather never said anything about my coming home late as this was a festival season and I was doing my "religious duty". I wished everyday was like those ten days of Dashain where I roamed freely and without care.

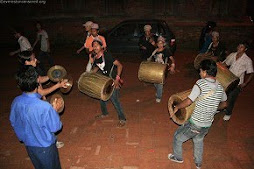

The atmosphere on the streets was worth the trouble getting up so early in the morning. You would see a folk band playing their traditional instruments marching toward or returning from the temples. Flutes, clarinets, drums and cymbals were the typical instruments played by the bands. Members of the brand had brightly colored red and yellow tika on their forehead, and marigold flowers on their heads or around their necks. As if the gods were hiding in the clouds and were cheering for these band, the whole atmosphere was joyous and spiritual; there was something sacred about it. The cool morning son glowed on cheerful faces; people seemed so content and happy as if they had forgotten all their troubles and left their cares behind. Growing up, I always cherished those solemn occasions and blissful moments, which remind me that life can be simple yet beautiful.

The festival of Dashain (also called Vijaya Dashami) is celebrated for ten days, the tenth day being the grand culmination of nine days of worshiping. It is the biggest festival of Nepal, when even the government shuts down for several days. In some ways, it is like Christmas when friends and relatives from far and wide meet and greet each other, families reunite, and past grievances are forgotten. My grandfather changed the furnishings at home and all of us received new clothes, shoes, sweets and money. On the tenth day, our family priest visited the house and after the rituals of worshipping and cleansing the house put red tika on our foreheads and the jamara (barley plants) which by now would be bright yellow and some six inches long. We would all gather in my grandfather’s room, all dressed in new clothes; the men and boys looked handsome and cheerful, women and girls looked elegant and beautiful in their clothes and gold jewelries. All of us would receive tika and jamara one by one from my grandfather; the tradition was to start with the elders down to the youngest member of the family. After the tika, we would all eat together; lunch was typically goat meat (the goat sacrificed either on the eighth (Asthami) or the ninth day (Navami) of Dashain), rice, the best vegetables that one could buy in the market that day, and pickled radish and cucumber. I was really happy to see all my family (my parents came home to Kathmandu) and felt great satisfaction to be surrounded by loved ones. I wished the day lingered for a little while longer.

On most occasions, I visited Shobha Bhagavati not for religious reasons but mostly to swim in the river. But during the festival of Dashain (it falls usually in early October and is celebrated for two weeks) my friends and I visited the temple every day from the first day of Ghatasthapana (which I briefly mentioned in my earlier posting) till the ninth day of Nava Ratri (in Sanskrit ninth night). Those were very memorable days. The temples would be very crowded early morning and we had to line up for hours to get inside the temple. So my friends would wake me up as early as 2:00 am in the morning by calling out my name very loud from the courtyard of our house. I would wake up (or sometimes it was my grandmother who would wake me up), clean myself, dress neatly and join the friends who would be waiting for me. We would then call a few more friends who had agreed to join us the day before, and then slowly head towards the temple. The earliest we could visit the better it was, for the line would be very short during that time. We would get inside the temple, do a quick prayer and then get out as fast as we could as the real fun was not to worship but to do people watching, especially watching girls of our own age, who would line up and wait for their turn to get in. We would just hang around casting glances here and there, looking for some familiar faces or just looking for a pretty face. This would go on for an hour or two, as we would visit other nearby temples, and my friends would tell stories of some macho adventures (like stealing fruits from neighborhood orchards or watching the latest Bollywood flick, or how certain girl seemed to have shown interest) or entertained us with their braggadocio. But the most rewarding of all this waking up early morning and gallivanting around was the stop at a teashop. During the festival seasons, teashops would open as early as four in the morning; drinking a hot cup of tea was always so much enjoyable during the cool autumn mornings that we would drink several cups depending on how much money we could collect between us. By the time I returned home I would have already spent six or seven hours with my friends. My grandfather never said anything about my coming home late as this was a festival season and I was doing my "religious duty". I wished everyday was like those ten days of Dashain where I roamed freely and without care.

The atmosphere on the streets was worth the trouble getting up so early in the morning. You would see a folk band playing their traditional instruments marching toward or returning from the temples. Flutes, clarinets, drums and cymbals were the typical instruments played by the bands. Members of the brand had brightly colored red and yellow tika on their forehead, and marigold flowers on their heads or around their necks. As if the gods were hiding in the clouds and were cheering for these band, the whole atmosphere was joyous and spiritual; there was something sacred about it. The cool morning son glowed on cheerful faces; people seemed so content and happy as if they had forgotten all their troubles and left their cares behind. Growing up, I always cherished those solemn occasions and blissful moments, which remind me that life can be simple yet beautiful.

The festival of Dashain (also called Vijaya Dashami) is celebrated for ten days, the tenth day being the grand culmination of nine days of worshiping. It is the biggest festival of Nepal, when even the government shuts down for several days. In some ways, it is like Christmas when friends and relatives from far and wide meet and greet each other, families reunite, and past grievances are forgotten. My grandfather changed the furnishings at home and all of us received new clothes, shoes, sweets and money. On the tenth day, our family priest visited the house and after the rituals of worshipping and cleansing the house put red tika on our foreheads and the jamara (barley plants) which by now would be bright yellow and some six inches long. We would all gather in my grandfather’s room, all dressed in new clothes; the men and boys looked handsome and cheerful, women and girls looked elegant and beautiful in their clothes and gold jewelries. All of us would receive tika and jamara one by one from my grandfather; the tradition was to start with the elders down to the youngest member of the family. After the tika, we would all eat together; lunch was typically goat meat (the goat sacrificed either on the eighth (Asthami) or the ninth day (Navami) of Dashain), rice, the best vegetables that one could buy in the market that day, and pickled radish and cucumber. I was really happy to see all my family (my parents came home to Kathmandu) and felt great satisfaction to be surrounded by loved ones. I wished the day lingered for a little while longer.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)