One day in Nawalpur several staff from my dad’s office decided that they needed to visit Narayan Ghat for some official business. The office had a Russian-made jeep (as I have said before everything that looked like the American “Jeep” was jeep to us). So I tagged along with my parents. I remember a few things about that trip. We all were cramped in the jeep, there could have been more than ten people on it. The jeep had trouble making over a steep hill near Daune Danda (this was the highest point between Narayan Ghat and Nawalpur), some of us had to get off so the driver could safely reach the hill top where he waited for us. From the hill looking down, we saw several black things along the Narayani riverbanks. We were told they were the crocodiles basking in the sun. At Narayan Ghat while the husbands attended to office duty, their families decided to go to the cinema. Indeed, cinema was a real treat for many of us including myself.

My grandfather used to take me with him every time he wanted to see a movie. He was a movie buff, and saw the same movie several times; back then going to the cinema was a major event, and was well-planned in advance. There were five theaters in Kathmandu Valley – Jay Nepal Chitraghar, Ranjana Cinema Hall and Biswo Jyoti in Kathmandu; Ashok Cinema in Patan; and Nava Durga Chitra Mandir in Bhaktapur. The ones in Kathmandu were 20 odd minutes from our house. Anyway, my grandfather made sure that I gave him company; as long as the kids were with their parents or an adult they could see movies for free. Most movies shown in the cinemas were from Bollywood. A typical Bollywood movie would be three hours long, the main story punctuated by several song and dance numbers. Bollywood songs were very popular in Kathmandu where they were repeatedly played out on Nepal Radio. My mother is from the south (Janakpur, a border town) so going to the cinema for her was a natural thing to do. Besides, movie was the only modern form of entertainment for many Nepalese as there was no television at that time. I was deeply influenced by Bollywood movies and songs. As it turns out, I had a talent for singing. I did not know back then, but it appears the talent for singing was passed from my mother'side of families. In my case, it was my mother. I will have some more postings on Bollywood movies and Hindi songs, as these were critical to my upbringing, and provide an interesting narrative to my memories.

So on a hot afternoon we all landed in Narayan Ghat’s cinema hall where “Balram Shree Krishna (1968 release) was playing. The story is about the Hindu god Krishna and his elder brother Balram, both make a formidable pair and fight the bad guys in the movie. Honestly, I don’t remember anything about the movie. What I remember is several moviegoers walked out frequently as the heat inside the cinema hall was almost unbearable. The sweat from neatly packed bodies in the theater, combined with the smoke from cigarettes made it impossible to watch the movie in one go. It turns out that the cinema hall was a newly converted warehouse, the ventilation was awful, and the fans far in between. But who would miss the chance to see such an exciting movie? During the movie,I went out only once and that was not because I wanted to get away from the heat but because I had to use the bathroom.

On another such occasion, my father and I visited our homestead in Chitwan, eight kilometers east from Narayan Ghat. My uncle had been living in Chitwan for some time and was taking care of the land. Our house was in the middle of the farm, it was a crudely built timber cottage with thatch grasses as roof. On the north side of the house there was a chicken pen and a goat corral. Our visit occurred during the rice harvesting season. I saw many people on our farm. I suppose they were either hired hands or neighbors who had come to help my uncle in exchange for his help at a later time. Some of them were using sickles to cut paddy, others were carrying the paddies which were neatly bundled and transported to a place near the house. It was my first time to witness a rice harvest. Villagers asked my father about me as this was the first time they had ever seen me. I tagged behind my dad, shying away from all the inquisitive eyes, and refraining myself from talking to them. Our farm land was adjacent to a dense forest (Barandabar); there were several tall Sal trees still standing on our land, remnants of what used to be a dense forest. Remember, both Nawalpur and Chitwan (combinedly Rapti Valley) were new settlements, where migrants from the central hills had moved in to seek their fortunes in the new promised land. Alas, no one had told them how difficult their life would be, what wild things they would encounter, and how some of them eventually would have to return to their original homes. Meanwhile, I was enjoying my very short visit to Chitwan; people seemed friendly and hardworking. There was no electricity, water came from the wells hand dug into the ground. Interestingly, the water table was very high; one could find water after digging a hole of about ten feet. People were singing (it is customary to sing while doing farm work) and chatting, as if the work was not hard but fun. I looked further away and saw blue mountains, far behind were the snow capped mighty Himalaya. The paddy fields were alternated by brightly colored mustard fields. There were green and yellow fields on the foreground, blue and white mountains in the background, clear blue sky overhead, and emerald green forest behind me. It felt like I was in a Bollywood dream sequence.

Sunday, August 30, 2009

A “Country” Paradise

While the trip to Nawalpur visiting my parents, as described in my previous posting, was quite thrilling, my stay there was almost uneventful. I liked the village. The Resettlement Office was a small building and nearby was my father’s government quarters. I recall it was mostly a small thatched roof cottage, but was spacious enough for us (my parents and my two sisters). The government office and a public elementary school were the only concrete buildings in the village. Even though I was expected to be there for two months, my parents decided that I should go to school, it was on odd time going to school, that is, I was enrolling two months before the final exams. I guess the school headmaster was impressed by the fact that I was from Kathmandu. Anyway, I started going to school everyday shortly before 10 am and until four pm.

From what I recall, the government office was almost at the center of the village, a little to the southwest was our cottage, the school was less than five minutes walk east from our cottage, and there were a few huts and cottages north of the office lined up on the main street. A few minutes down the street (east direction) was the graveled highway to Narayanghat. The village was nothing more than a hamlet established in the middle of the dense jungle growth. Aside from going to school, there was not much else to do. I started hanging out with some local boys (I don’t know if they were transplanted just like me) and explored nearby places. The school was perched upon a hill. It was not really a hill, the dirt track from the highway dipped a little bit rising as it reached the village center. Just before the rise, one had to cross a small stream, toward the left a track led up to the school. I remember spending hours with some friends wading in the shallow pools of water and trying to catch fish with our tiny hands. The water was knee deep and clear, you could see the pebbles on the bottom and the fish running in unison in different directions. It gave me immense pleasure to see the small fish trying to escape from our hands, the cool touch of water (even though it was a Fall season, afternoon temperatures could be very high in the Terai), and the jungle surroundings. My days were carefree, pampered, and I always found something to do. Sometimes we visited the government-owned barn where we could pay a visit to a large brown horse. This was also the first time I rode a horse, I didn't last very long on horseback.

All in all, life in the country was completely different from Kathmandu. It was peaceful, harmonious and without events, except for one night when it seemed the whole village was going in flames. The Fall season in Terai is usually very dry except for the morning dews. So one night, as we were finishing our dinner we saw flames rising above us. One of the houses north from ours was up in flames, I recall vividly how high the flames were rising. The flames were twisting and twirling like Shiva’s furious dance moves, everyone was out, some were trying to help put out the fire, others were standing shell-shocked. In a matter of minutes the house was burnt to the ground. Next morning I went out with my parents to check the aftermath of the fire and to express our sympathies to the family. The place was covered with black soot and hardly anything was left worth salvaging. I felt very bad for the family, one of their girls was in the same class that I was in (Grade Four). The Year was 1969.

From what I recall, the government office was almost at the center of the village, a little to the southwest was our cottage, the school was less than five minutes walk east from our cottage, and there were a few huts and cottages north of the office lined up on the main street. A few minutes down the street (east direction) was the graveled highway to Narayanghat. The village was nothing more than a hamlet established in the middle of the dense jungle growth. Aside from going to school, there was not much else to do. I started hanging out with some local boys (I don’t know if they were transplanted just like me) and explored nearby places. The school was perched upon a hill. It was not really a hill, the dirt track from the highway dipped a little bit rising as it reached the village center. Just before the rise, one had to cross a small stream, toward the left a track led up to the school. I remember spending hours with some friends wading in the shallow pools of water and trying to catch fish with our tiny hands. The water was knee deep and clear, you could see the pebbles on the bottom and the fish running in unison in different directions. It gave me immense pleasure to see the small fish trying to escape from our hands, the cool touch of water (even though it was a Fall season, afternoon temperatures could be very high in the Terai), and the jungle surroundings. My days were carefree, pampered, and I always found something to do. Sometimes we visited the government-owned barn where we could pay a visit to a large brown horse. This was also the first time I rode a horse, I didn't last very long on horseback.

All in all, life in the country was completely different from Kathmandu. It was peaceful, harmonious and without events, except for one night when it seemed the whole village was going in flames. The Fall season in Terai is usually very dry except for the morning dews. So one night, as we were finishing our dinner we saw flames rising above us. One of the houses north from ours was up in flames, I recall vividly how high the flames were rising. The flames were twisting and twirling like Shiva’s furious dance moves, everyone was out, some were trying to help put out the fire, others were standing shell-shocked. In a matter of minutes the house was burnt to the ground. Next morning I went out with my parents to check the aftermath of the fire and to express our sympathies to the family. The place was covered with black soot and hardly anything was left worth salvaging. I felt very bad for the family, one of their girls was in the same class that I was in (Grade Four). The Year was 1969.

Monday, August 10, 2009

Trouble in Paradise

I guess, it was “written” that I would become a professor of tourism, specializing on management of natural resources and tourism impacts in remote areas. I find it rather interesting how early encounters with wildlife shape future careers. The curiosity about places other than my own hometown planted in me a seed for my future adventures, some of which were utterly reckless. Encounters with wildlife also started with a bizarre set of events. As I wrote in a previous posting, I am really afraid of snakes. I am curious about snakes, thrilled to see it crawling (this makes hair on my spine stand up!), but will not go closer even if it is dead. My mom tells me that when I was a two-month old baby, she had taken me to Khajuri where all kinds of venomous snakes crawled around. King Cobras were common; I am fortunate not to have seen it in the wild. I have seen big Dhamans (Ptyas mucosus) on the banks of Devata Pokhari. So my mom puts me on bed for an afternoon nap. My grandparent’s house in Khajuri consisted of two modest buildings. The walls were made of a reed-mud combination and the roof had cylindrical-shaped tiles. The two buildings were separated by a courtyard in the middle and gardens on the sides. It was a custom in the village to spend the afternoon mostly in the verandah or the courtyard because it would get terribly hot during summer. Anyway, I was sleeping on a make-shift bed on the ground. All of a sudden, there was a big snake underneath my bed. Everybody was panicking and did not know what to do, no one dared to come close to me. So there I was surrounded by a big snake, and I could do nothing about it (my mom told me that I was sound asleep). Fortunately, the snake slithered away after sometime and everybody rejoiced that nothing bad happened to me. May be snake phobia is in my genes, as I know that my mom and I react exactly the same way whenever we see a snake.

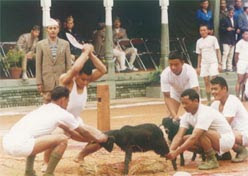

Thus, encounters with wildlife were something that came natural to me. Chitwan in the late 60s and early 70s was pretty much a wild place. People had this notion that there were more wild things in Chitwan than people. Our house in Chitwan back then was very rudimentary, made mostly of wood and thatch grasses. This was a temporary house as most of our family members (except my uncle) lived in Kathmandu. My dad was temporarily assigned to Chitwan. The year must have been 1973. I remember when I was 11 we had a bad incident in our homestead in Chitwan. Back then, we used to keep many chickens (around 200) and we had two pairs of goats, one pair was skinny than the other. One night, my dad saw a pair of glowing eyes in the dark as he went out to relieve himself. He did not know what exactly the animal was but the following morning we found that a pair of goats was missing from the corral. The whole family went out to search for the missing goats, and lo and behold!, we found the mother goat lying dead in the field. She had been blood-sucked dry and there was a fatal mark around her neck. The kid goat was nowhere to be found. Later in the afternoon, my uncle found its head at the edge of our field (the edge marks the boundaries between our land and the Barandabar forest). Villagers gathered in our house concluded that it must have been the clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa) who had snatched away the goats. There were also rumours about witchcraft, but it seemed to us that the culprit in this case was not a poor woman in the village but a nasty leopard. The leopard must have been really smart as he chose the two healthy (fat) ones and not the skinny ones; they were left untouched, they seemed very sacred though. This was my earliest exposure to human-wildlife conflict in Chitwan, a topic which would become one of my major research themes in my future academic career. I would come back to this issue ten years later as an academic researcher.

Thus, encounters with wildlife were something that came natural to me. Chitwan in the late 60s and early 70s was pretty much a wild place. People had this notion that there were more wild things in Chitwan than people. Our house in Chitwan back then was very rudimentary, made mostly of wood and thatch grasses. This was a temporary house as most of our family members (except my uncle) lived in Kathmandu. My dad was temporarily assigned to Chitwan. The year must have been 1973. I remember when I was 11 we had a bad incident in our homestead in Chitwan. Back then, we used to keep many chickens (around 200) and we had two pairs of goats, one pair was skinny than the other. One night, my dad saw a pair of glowing eyes in the dark as he went out to relieve himself. He did not know what exactly the animal was but the following morning we found that a pair of goats was missing from the corral. The whole family went out to search for the missing goats, and lo and behold!, we found the mother goat lying dead in the field. She had been blood-sucked dry and there was a fatal mark around her neck. The kid goat was nowhere to be found. Later in the afternoon, my uncle found its head at the edge of our field (the edge marks the boundaries between our land and the Barandabar forest). Villagers gathered in our house concluded that it must have been the clouded leopard (Neofelis nebulosa) who had snatched away the goats. There were also rumours about witchcraft, but it seemed to us that the culprit in this case was not a poor woman in the village but a nasty leopard. The leopard must have been really smart as he chose the two healthy (fat) ones and not the skinny ones; they were left untouched, they seemed very sacred though. This was my earliest exposure to human-wildlife conflict in Chitwan, a topic which would become one of my major research themes in my future academic career. I would come back to this issue ten years later as an academic researcher.

Saturday, August 8, 2009

Way to Paradise

Well, it was not just Thamel that was changing fast. The whole country was experiencing change. I had some first hand insights to some of these changes that were going on outside the capital city.

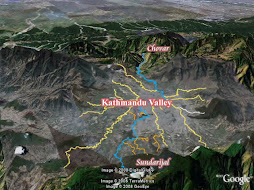

By now, you must have figured out that I spent my formative years mostly with my grandparents. My dad was a government employee (department of Agriculture) and he was stationed outside the valley, so my mother had to accompany him wherever my dad’s job took him. In the late 60s, my dad worked for the Rapti Valley Resettlement Project in Nawalpur (Nawal Parasi District) in the Terai. There were no roads to Chitwan (a neighboring district on the western edge of the Narayani River). From Kathmandu, the ride involved taking the bus to Hetaunda (a small market town about 100 km south of the Valley) via the Tribhuvan Highway (Kathmandu-Birgunj), then taking the bus (I am not sure if a regular bus service existed then) on the dirt road to Narayan Ghat, then taking the ferry across the Narayani River, switch to another bus and continue further toward Parasi. I have vague recollections of my first road trip outside the Valley. My previous visit to Janakpur was on an airplane flight of which I remember nothing.

Anyway, it so happened that my father’s officemate was in Kathmandu for a visit to the Department of Agriculture. As he had traveled from Nawalpur on an official car, my parents had requested that he visit our house in Paknajole, and take me with him to Nawalpur if my grandfather granted his approval. So this offical (and I suppose the driver) came to our house, talked to my grandparents who asked me to be ready for this very long journey to the Terai. It must have been hard for my grandfather to let me go as he did not have a strong liking of places outside Kathmandu and he certainly did not like the malaria-infested (which had been eradicated in the 50s) hot tropical lowlands. Anyway, we were soon on the road to Chitwan. I was very excited about this trip, not only was I looking forward to meeting my parents after a long time, but I was also very curious about the road journey and the new places that I would be seeing. As a three year old boy, I had enjoyed my trip to Janakpur. This time I was older (7 years old) and was ready for the adventure. I was given two tablets to drink lest I fall sick on the road. I don’t remember much after that. What I do remember is that the road from Hetaunda to Narayan Ghat was basically a dirt road, and could be travelled only on a four wheel drive like the ones we were riding. It was already dark by the time we reached Hetaunda. The Tribhuvan Highway is a treacherous road, rising up and down the valley with numerous hairpin curves and then reaching to a height of nearly 8,000 ft above sea level at Sim Bhanjyang (almost a mid-point between Kathmandu and Hetaunda; on a clear day it is possible to see the summit of Mt. Everest from Daman, the hill below Sim Bhanjyang). The journey was scary but fun.

It all felt very strange once we hit the road from Hetaunda toward Chitwan. Chitwan, as a physical location does not exist, it is a District and not a town or a village. But people made frequent references to Chitwan and not Naraya Ghat or Bharatpur where the district headquarter is located. Anyway, the jeep was traveling on a dirt track which was hardly wider than ten feet. There were trees and stumps all over the place, so the driver had to carefully navigate the jeep through the jungle. We had to cross numerous ravines and rivers. Chitwan was still densely forested (it is the home of the famous Chitwan National Park and the Tikauli (Barandabar) forest), punctuated by small hamlets dotted by thatch-roofed huts. I remember vividly that the driver would draw our attention to the glowing eyes in the dark (I learnt later that they were the eyes of sambar deer (Axis axis), and howls of wild animals. Chitwan was, and still is, famous for tigers, rhinoceros, crocodiles and other big-game mammals, so I was thrilled (honestly, I was afraid) to be on the road. We came to our stop for the night somewhere in the middle of the jungle (I think it was Bharatpur but I am not sure about it). The following morning we went down to the river at Narayan Ghat, which back then was mostly a collection of thatch-roofed houses. I do not remember seeing a concrete house, or may be I just did not see that part of the town. Anyway, our jeep was loaded on to the ferry boat. The interesting this about the ferry was two boats (timber construction) were tied together to make them wide enough to load vehicles. The river was big; I had not seen anything like that before. The view was just marvelous. So we were on the boat and a few minutes after we were on the Nawal Parasi side of the river. The jeep was unloaded, and after crossing a shallow section of the river we were back on the dirt road. I don’t remember how or what time did we arrive at Nawalpur. What I remember is that from a hill top (Daunne Danda), one could see the Narayani river below and its numerous sandbanks; the view toward Chitwan was just magnificent – it was densely packed with tall trees (mostly Sal (Shorea robusta)). Nearby, I could see the dense undergrowth, tall trees of all shapes and forms, and numerous climbers and creepers hanging on to the trees.

This journey had left a vivid impression on me. Here I was, a seven year old boy from the city, partaking in an adventurous, occasionally hair-raising, jeep ride through one of the last vestiges of pristine forests in the country. The scenery everywhere was wild and beautiful, the road interrupted by numerous clear-bottom streams in which little fish swam peacefully, the air crisp but humid, the cries from the wild strange and mysterious. This was in total contrast to what I was used to in the city. I thought I was in paradise!

By now, you must have figured out that I spent my formative years mostly with my grandparents. My dad was a government employee (department of Agriculture) and he was stationed outside the valley, so my mother had to accompany him wherever my dad’s job took him. In the late 60s, my dad worked for the Rapti Valley Resettlement Project in Nawalpur (Nawal Parasi District) in the Terai. There were no roads to Chitwan (a neighboring district on the western edge of the Narayani River). From Kathmandu, the ride involved taking the bus to Hetaunda (a small market town about 100 km south of the Valley) via the Tribhuvan Highway (Kathmandu-Birgunj), then taking the bus (I am not sure if a regular bus service existed then) on the dirt road to Narayan Ghat, then taking the ferry across the Narayani River, switch to another bus and continue further toward Parasi. I have vague recollections of my first road trip outside the Valley. My previous visit to Janakpur was on an airplane flight of which I remember nothing.

Anyway, it so happened that my father’s officemate was in Kathmandu for a visit to the Department of Agriculture. As he had traveled from Nawalpur on an official car, my parents had requested that he visit our house in Paknajole, and take me with him to Nawalpur if my grandfather granted his approval. So this offical (and I suppose the driver) came to our house, talked to my grandparents who asked me to be ready for this very long journey to the Terai. It must have been hard for my grandfather to let me go as he did not have a strong liking of places outside Kathmandu and he certainly did not like the malaria-infested (which had been eradicated in the 50s) hot tropical lowlands. Anyway, we were soon on the road to Chitwan. I was very excited about this trip, not only was I looking forward to meeting my parents after a long time, but I was also very curious about the road journey and the new places that I would be seeing. As a three year old boy, I had enjoyed my trip to Janakpur. This time I was older (7 years old) and was ready for the adventure. I was given two tablets to drink lest I fall sick on the road. I don’t remember much after that. What I do remember is that the road from Hetaunda to Narayan Ghat was basically a dirt road, and could be travelled only on a four wheel drive like the ones we were riding. It was already dark by the time we reached Hetaunda. The Tribhuvan Highway is a treacherous road, rising up and down the valley with numerous hairpin curves and then reaching to a height of nearly 8,000 ft above sea level at Sim Bhanjyang (almost a mid-point between Kathmandu and Hetaunda; on a clear day it is possible to see the summit of Mt. Everest from Daman, the hill below Sim Bhanjyang). The journey was scary but fun.

It all felt very strange once we hit the road from Hetaunda toward Chitwan. Chitwan, as a physical location does not exist, it is a District and not a town or a village. But people made frequent references to Chitwan and not Naraya Ghat or Bharatpur where the district headquarter is located. Anyway, the jeep was traveling on a dirt track which was hardly wider than ten feet. There were trees and stumps all over the place, so the driver had to carefully navigate the jeep through the jungle. We had to cross numerous ravines and rivers. Chitwan was still densely forested (it is the home of the famous Chitwan National Park and the Tikauli (Barandabar) forest), punctuated by small hamlets dotted by thatch-roofed huts. I remember vividly that the driver would draw our attention to the glowing eyes in the dark (I learnt later that they were the eyes of sambar deer (Axis axis), and howls of wild animals. Chitwan was, and still is, famous for tigers, rhinoceros, crocodiles and other big-game mammals, so I was thrilled (honestly, I was afraid) to be on the road. We came to our stop for the night somewhere in the middle of the jungle (I think it was Bharatpur but I am not sure about it). The following morning we went down to the river at Narayan Ghat, which back then was mostly a collection of thatch-roofed houses. I do not remember seeing a concrete house, or may be I just did not see that part of the town. Anyway, our jeep was loaded on to the ferry boat. The interesting this about the ferry was two boats (timber construction) were tied together to make them wide enough to load vehicles. The river was big; I had not seen anything like that before. The view was just marvelous. So we were on the boat and a few minutes after we were on the Nawal Parasi side of the river. The jeep was unloaded, and after crossing a shallow section of the river we were back on the dirt road. I don’t remember how or what time did we arrive at Nawalpur. What I remember is that from a hill top (Daunne Danda), one could see the Narayani river below and its numerous sandbanks; the view toward Chitwan was just magnificent – it was densely packed with tall trees (mostly Sal (Shorea robusta)). Nearby, I could see the dense undergrowth, tall trees of all shapes and forms, and numerous climbers and creepers hanging on to the trees.

This journey had left a vivid impression on me. Here I was, a seven year old boy from the city, partaking in an adventurous, occasionally hair-raising, jeep ride through one of the last vestiges of pristine forests in the country. The scenery everywhere was wild and beautiful, the road interrupted by numerous clear-bottom streams in which little fish swam peacefully, the air crisp but humid, the cries from the wild strange and mysterious. This was in total contrast to what I was used to in the city. I thought I was in paradise!

Thursday, August 6, 2009

Paradise Lost

I remember how Thamel used to be in the late 60s and early 70s. The first ever school that I attended was the venerable Juddhodaya Public High School. Popularly, and affectionately, known as JP, it was a public school in the afternoon but was a private English school in the morning. The English school was run by a very strict but highly effective principal whose first name I do not remember very well. I do remember he was a Gurung man. His wife was very active too and their two sons were also enrolled at the same school. I started in Grade 5 (I was eight years old at that time) – the year must have been 1970. There were three different routes to the school, a short route via Thamel (past the Kathmandu Guest House), a longer route via Chetrapati, and another longer route via Sorahkhutte. The route we would select would depend on my friends who would be walking with me to the school; mind you, I was the youngest in class. We had to be inside the school compound by 6 am in the morning, too early for an eight year old, however, I was already used to waking up early in the morning (five to be exact). So, I would (or it was rather my grandmother) pack my bags and walk toward the school, a few boys would be either waiting for me down the street or would catch up in case they were late. One of my classmates, Chandra Gurung (I affectionately called him Chandre), was slightly older than me, perhaps by two years. He lived in a rented apartment in Sorahkhutte, so I used to call him up from the street. We then would walk to the school together via Thamel. Sometimes, he would come early, call me up in my house, and then we would go to school via Chetrapati. The shorter route to the school was via Saat Ghumti (street with seven corners), which was behind KGH, but unless we were really late we would never go that way. The main reason was that Saat Ghumti always seemed narrow (it was not on the main street) and dark (no pole lights), and our elders would advise us little children to take a safer route instead. We used to take that route occasionally, usually when we were going to be late to school. We would rather take the risk of walking the dark street than being late to school, in case of which we were certain to receive some form of punishment. So, we would run past Saat Ghumti (occasionally looking behind if someone was following), walk briskly past the (east) entrance to KGH, and then slow down a bit to come to our senses, celebrate our victory of overcoming fear, and then calmly walk past the school entrance.

Today when I think about those days, especially the dreaded walk past Saat Ghumti and the fear of being chased by some hooligans or an imaginary ghost (we had heard plenty of ghost stories), I am forced to laugh at myself and my foolish friends. What a chicken we had been! But would you really blame an eight year old for being a chicken, you won’t, right? Anyway, the point is Thamel of the past was not what it has become today, a real world for the tourists, a fantasy land for the locals, with all its neon lights, foreigners and foreign food, departmental stores, clubs, and what not. More on this will come later. For now, let’s stay focused on land use change in and around Thamel. Two popular hotels – Manang at the northern edge of Thamel (toward Sorahkhutte Pati) and Marsyangdi, a few blocks north of KGH – were built by entrepreneurs from Manang (a hill district in the shadow of the Great Himalaya in central Nepal). They purchased the vacant land from people I knew. By the way, Sorahkhutte means sixteen legged, and pati means a shelter (more like a pavilion). There is an interesting story of such patis in the Valley. The patis were the inns of yesteryears . The Z Street, which today connects Thamel with Paknajole, used to be the vegetable garden where we stomped. A big white-washed residence in Thamel, which belonged to a Thakali family who had extensive properties around the country including in Chitwan, is now gone. Today, it is replaced by a collection of buildings outfitted with restaurants, retail shops, bank, travel and trekking agency, cargo agent, etc. A big compound northeast from Thakali’s residence has now a hotel in it (Hotel Vaishali). I had a friend in school (he was a couple grades higher than me) who lived in a house inside that compound. The land owned by our neighbors in Paknajole – the Thakuri family – now has several hotels, a spa, a restaurant and other businesses. There are hotels and restaurants of all kinds and names everywhere. And there is the Cheap Heaven Restaurant!. I wonder what kind of heaven is the owner selling. To me, the paradise as it used to exist, has been lost already. The green space that I saw, experienced, felt, touched and played upon has long since been gone. There are concrete buildings and neon lights everywhere, and new billboards have sprung up as if to proclaim the seasons'offerings of bits of paradise. Thamel has become the land of excess and absurdities, where Buddha can be cool and funky!

To be continued...

Today when I think about those days, especially the dreaded walk past Saat Ghumti and the fear of being chased by some hooligans or an imaginary ghost (we had heard plenty of ghost stories), I am forced to laugh at myself and my foolish friends. What a chicken we had been! But would you really blame an eight year old for being a chicken, you won’t, right? Anyway, the point is Thamel of the past was not what it has become today, a real world for the tourists, a fantasy land for the locals, with all its neon lights, foreigners and foreign food, departmental stores, clubs, and what not. More on this will come later. For now, let’s stay focused on land use change in and around Thamel. Two popular hotels – Manang at the northern edge of Thamel (toward Sorahkhutte Pati) and Marsyangdi, a few blocks north of KGH – were built by entrepreneurs from Manang (a hill district in the shadow of the Great Himalaya in central Nepal). They purchased the vacant land from people I knew. By the way, Sorahkhutte means sixteen legged, and pati means a shelter (more like a pavilion). There is an interesting story of such patis in the Valley. The patis were the inns of yesteryears . The Z Street, which today connects Thamel with Paknajole, used to be the vegetable garden where we stomped. A big white-washed residence in Thamel, which belonged to a Thakali family who had extensive properties around the country including in Chitwan, is now gone. Today, it is replaced by a collection of buildings outfitted with restaurants, retail shops, bank, travel and trekking agency, cargo agent, etc. A big compound northeast from Thakali’s residence has now a hotel in it (Hotel Vaishali). I had a friend in school (he was a couple grades higher than me) who lived in a house inside that compound. The land owned by our neighbors in Paknajole – the Thakuri family – now has several hotels, a spa, a restaurant and other businesses. There are hotels and restaurants of all kinds and names everywhere. And there is the Cheap Heaven Restaurant!. I wonder what kind of heaven is the owner selling. To me, the paradise as it used to exist, has been lost already. The green space that I saw, experienced, felt, touched and played upon has long since been gone. There are concrete buildings and neon lights everywhere, and new billboards have sprung up as if to proclaim the seasons'offerings of bits of paradise. Thamel has become the land of excess and absurdities, where Buddha can be cool and funky!

To be continued...

Tuesday, August 4, 2009

Paving Paradise

My recent visit to Kathmandu evoked many memorable events from the past. I was in Montreal in September 1994 attending a global conference on tourism. I met a guy from New York who had been to Nepal in the 70s and had loved visiting there. He remembered his visit to Pashupatinath Temple and told me that he had discovered “paradise on earth”. I will tell you that during the 70s Nepal was a very popular destination for the hippies; maurijauna (ganza in Nepali), cannabis (hashish) were readily available in tourist areas such as the infamous “Freak Street” (Jhonche Tole). My friend from New York probably had smoked some ganza (resident Sadhus in Pashupati smoked it openly) as he must have felt the smoke lifting him to cloud nine. Local newspapers would report widespread use of other potent drugs like crack cocaine, heroin, and LSD (Lysergic Acid Diethylamide) amongst tourists and locals mostly who associated with tourists. Movies capitalized on the drug culture. I remember watching the movie “LSD” (not sure about the country where this was made) at a local theater. Dev Anand (the Gary Cooper of Bollywood) made a very popular movie “Hare Rama Hare Krishna” which was entirely filmed in tourist locations in Kathmandu. So, if you liked joints and grew up in the 70s and visited Kathmandu, I bet you felt there was no better place on earth.

However, the point of this post is not to dwell on the drug culture of Kathmandu but to talk about the loss of open space in and around my neighborhood. As I wrote in my previous blog, my friends and I would fool around and engage in all kinds of mischiefs. Stealing plums and persimmons from neighbor’s orchards, marauding vegetable gardens looking for the best radish (long and red – I haven’t seen this variety outside Kathmandu) and succulent cucumbers to eat while we played, were our favorite pass times . As Jhonche was getting notorious for its drug-infested tourist culture, Thamel (which was only a block or two away from our house in Paknajole) was gradually prospering as a tourist center. The legendary Kathmandu Guest House (KGH), run by the Shakya family, was the oldest establishment in Thamel. Two restaurants – Utse (Tibetan food, my favorite restaurant as I grew older) and KC’s (mostly western fares) - were the oldest restaurants in Thamel. But as the 70s waned, Thamel saw dramatic changes in its built-up areas, newer and larger houses were built to provide tourist accommodations. The main street in Thamel leading to the KGH used to be poorly lit and deemed unsafe to walk at night (we would avoid it after six in the evening). But now with new constructions and expanding tourist establishments, orchards and vegetable gardens were slowly giving way to multi-story buildings. I used to spend hours playing with my friends in the vegetable gardens (this was tolerated during off-seasons when no vegetables were planted). Suddenly, our favorite playgrounds were off-limits to us, and our daily routines affected as we started looking for alternative venues, further away from our neighborhood. Kathmandu was certainly experiencing a construction boom and it seemed Thamel was the epicenter of that boom. Our own family garden in front of our house was lost, as we had to forego our rights to plant vegetables there due to legal disputes with our neighbors who claimed the small parcel of land as communal property. Our neighbor behind our house had a big chunk of land where the family would grow vegetables. They sold their entire property to a guy who decided to construct a hotel. Tourist developments were slowly changing the landscape around Thamel, and the sights of tourists were becoming much more frequent. It was not until about the mid-1980s that tourism really took a strong hold in Thamel. But it was long before that all vacant plots and green space succumbed to the pressures of touristic enterprise and aspirations.

More on landuse change later...

However, the point of this post is not to dwell on the drug culture of Kathmandu but to talk about the loss of open space in and around my neighborhood. As I wrote in my previous blog, my friends and I would fool around and engage in all kinds of mischiefs. Stealing plums and persimmons from neighbor’s orchards, marauding vegetable gardens looking for the best radish (long and red – I haven’t seen this variety outside Kathmandu) and succulent cucumbers to eat while we played, were our favorite pass times . As Jhonche was getting notorious for its drug-infested tourist culture, Thamel (which was only a block or two away from our house in Paknajole) was gradually prospering as a tourist center. The legendary Kathmandu Guest House (KGH), run by the Shakya family, was the oldest establishment in Thamel. Two restaurants – Utse (Tibetan food, my favorite restaurant as I grew older) and KC’s (mostly western fares) - were the oldest restaurants in Thamel. But as the 70s waned, Thamel saw dramatic changes in its built-up areas, newer and larger houses were built to provide tourist accommodations. The main street in Thamel leading to the KGH used to be poorly lit and deemed unsafe to walk at night (we would avoid it after six in the evening). But now with new constructions and expanding tourist establishments, orchards and vegetable gardens were slowly giving way to multi-story buildings. I used to spend hours playing with my friends in the vegetable gardens (this was tolerated during off-seasons when no vegetables were planted). Suddenly, our favorite playgrounds were off-limits to us, and our daily routines affected as we started looking for alternative venues, further away from our neighborhood. Kathmandu was certainly experiencing a construction boom and it seemed Thamel was the epicenter of that boom. Our own family garden in front of our house was lost, as we had to forego our rights to plant vegetables there due to legal disputes with our neighbors who claimed the small parcel of land as communal property. Our neighbor behind our house had a big chunk of land where the family would grow vegetables. They sold their entire property to a guy who decided to construct a hotel. Tourist developments were slowly changing the landscape around Thamel, and the sights of tourists were becoming much more frequent. It was not until about the mid-1980s that tourism really took a strong hold in Thamel. But it was long before that all vacant plots and green space succumbed to the pressures of touristic enterprise and aspirations.

More on landuse change later...

Saturday, August 1, 2009

Down the memory lane

Memories are powerful things, specially those from early years of your life. Some people, like myself, cling to their childhood memories as they seek to find their roots, or their identity. Whatever is one looking for - cherished and dreaded moments - traveling down the memory lane is always fun. I like to remember the sweet times that I enjoyed, the occasional embarrassing moments that I wished never occurred, moments that I wished lingered for a little while, and so on. I still remember my days in Khajuri as a three year old boy visiting my mother’s side of the family for the first time. It was not really the first time I had visited my grandparent’s family, I was there as a two-month old baby, but this I don’t remember. So you see, memory lanes can hit a dead end. Now, some people may ask how come I remember things that happened so long ago in my life. I do not claim to remember everything, what I remember are snippets of some visual imageries. When I returned later as a 13 year old, things that I saw in Khajuri confirmed that my earlier memories were fairly accurate.

I remembered the location of my grandparent’s house (not the details of the house though). The house was perched above from a pond; a narrow path led to the stairs (brick-paved) to the pond. On top of the stairs was the southern entrance to the templeyard; access to the main temple was through a mango orchard. The pond was popularly known as Devata Pokhari (God’s Pond). Behind the house (to the east) was a big Jamun tree (Syzygium cumini), an evergreen tropical flowering tree native to Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Indonesia. The Jamun fruit (a small, purple colored plum) is simply delicious. These images were implanted in my memories so strongly that the ponds, temple and the tree were the three major things I was expecting to see in my future visits to Khajuri, which would occur only in 1976, more than ten years after my first visit there. Everytime I heard something about Khajuri, the first thing that came to my mind were the ponds, the Jamun tree, and the dirt path leading to my grandparents’ house. It’s interesting that the surroundings in Khajuri fascinated me. It seemed the perfect place for a kid to grow up – swimming in the ponds, eating Jamun and mangoes, kicking dirt, and living carefree. I had no memories of the train ride that we had to take from Janakpur (a town in the southern lowlands of Nepal) to Khajuri, but I do remember my mother’s attempts to cheer me and my younger sister during our photo session at a studio in Jay Nagar (a border town in India). My sister was crying, and was not cooperating with the photographer, so he gave her a small doll to hold. I don’t remember how long we spent at the studio, but he was able to take our photo (hand painted in color!). I also remember the strong smell of urine on the street on our way to my aunt’s (my mom’s eldest sister) apartment in town. Jay Nagar is at the terminus of the Indian railway. The smell of coal and steam, coupled with the southern heat, created a strange odor in the air. It did not occur to me at that time that the air we were breathing was perhaps polluted. On the contrary, I found the smell of the coal in the air to be very pleasant.

To sum up, my early memories of Khajuri consisted of 1) physical objects: ponds, trees, temples, and 2) sensory: the strong smell of urine and coal in Jay Nagar. Overall, it must have been a pleasant visit, as I always longed to return to Khajuri.

I remembered the location of my grandparent’s house (not the details of the house though). The house was perched above from a pond; a narrow path led to the stairs (brick-paved) to the pond. On top of the stairs was the southern entrance to the templeyard; access to the main temple was through a mango orchard. The pond was popularly known as Devata Pokhari (God’s Pond). Behind the house (to the east) was a big Jamun tree (Syzygium cumini), an evergreen tropical flowering tree native to Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Indonesia. The Jamun fruit (a small, purple colored plum) is simply delicious. These images were implanted in my memories so strongly that the ponds, temple and the tree were the three major things I was expecting to see in my future visits to Khajuri, which would occur only in 1976, more than ten years after my first visit there. Everytime I heard something about Khajuri, the first thing that came to my mind were the ponds, the Jamun tree, and the dirt path leading to my grandparents’ house. It’s interesting that the surroundings in Khajuri fascinated me. It seemed the perfect place for a kid to grow up – swimming in the ponds, eating Jamun and mangoes, kicking dirt, and living carefree. I had no memories of the train ride that we had to take from Janakpur (a town in the southern lowlands of Nepal) to Khajuri, but I do remember my mother’s attempts to cheer me and my younger sister during our photo session at a studio in Jay Nagar (a border town in India). My sister was crying, and was not cooperating with the photographer, so he gave her a small doll to hold. I don’t remember how long we spent at the studio, but he was able to take our photo (hand painted in color!). I also remember the strong smell of urine on the street on our way to my aunt’s (my mom’s eldest sister) apartment in town. Jay Nagar is at the terminus of the Indian railway. The smell of coal and steam, coupled with the southern heat, created a strange odor in the air. It did not occur to me at that time that the air we were breathing was perhaps polluted. On the contrary, I found the smell of the coal in the air to be very pleasant.

To sum up, my early memories of Khajuri consisted of 1) physical objects: ponds, trees, temples, and 2) sensory: the strong smell of urine and coal in Jay Nagar. Overall, it must have been a pleasant visit, as I always longed to return to Khajuri.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)